I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

It is always better to tell the truth

The Austrians are lying about my country. They generally lie about everything but when it comes to my own nation of which I know the data very well then something has to be done. Today I examine the claim by some Austrians out there that the Reserve Bank of Australia cannot unilaterally create $A dollar credits in the banking system (for example, add to bank reserves) without first holding American dollars (or for that matter any currency). The claim is totally nonsensical but you need to first understand how central banks operate and then form an accurate view of the historical record to understand why. But when it comes to using publicly available data that other “experts” know very well – it is always better to tell the truth. I am on a bit of a truth theme over the last week.

A regular Billy Blog reader was puzzled by a blog (June 6, 2011) that he had read entitled Why You Need American Dollars to Mint Australian Ones – which was published by some group calling itself the Center for Geoeconomic Studies (hereafter the “Center”).

This “Center” describes its mission as being:

… to promote a better understanding among policymakers, academic specialists, and the interested public of how economic and political forces interact to influence world affairs.

To succeed in that mission you need two assets: (a) some basic understanding; (b) the capacity to tell the truth and not engage in distortion.

The “Center” is missing at least one of those assets if its work is anything to go by. Let’s be kind to them and assume it is (a). So despite them listing a plethora of “experts” on their Home Page, we might – being kind – assume they are dumb.

The blog in question wants to be cute and challenge the notion that “All countries with central banks exercise monetary sovereignty, right?”. They use the column to attack Paul Krugman for daring to agree with that proposition.

First, here is an indisputable fact.

Central banks are creatures of government despite all the rhetoric that you read about them being independent. They are “independent” at the government’s pleasure.

Please read my blog – Central bank independence – another faux agenda – for more discussion on this point.

If you want the chapter and verse then the Reserve Bank Act 1959 is worth reading. For example, to see who is boss you might like to read Section 11 – Differences of opinion with Government on questions of policy. If there is a disagreement then after consultation between the Treasurer and the RBA, the former can then submit a recommendation to the Governor-General who determines “the policy to be adopted by the Bank”.

Then the “Treasurer would … inform the Reserve Bank Board of the policy so determined and the Board would be obliged to implement it.”

The Governor-General is appointed by the Government of the day.

Section 24 also tells us that the Governor and the Deputy Governor of the RBA “are to be appointed by the Treasurer” as is the RBA Board.

Second, from a macroeconomic perspective Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) starts its journey by delineating the transactions that occur between the government and the non-government sector. It is imperative that the central bank and treasury operations be treated in a consolidated manner for a correct understanding.

Please read my blog – The consolidated government – treasury and central bank – for more discussion on this point.

There is also a full discussion in the blog – Deficits 101 Part 3 – and that blog was a summary of the material originally presented in my book Full Employment Abandoned: Shifting sands and policy failures which was published in 2008.

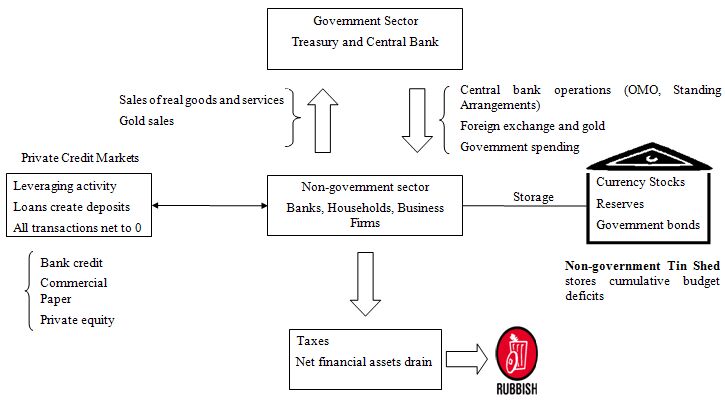

The following diagram was presented to elaborate on the vertical transactions between the government and non-government sectors and to explain the importance of them for understanding how the economy works?

If we just focus on the vertical transactions (from top to bottom of the diagram) you will see that the tax liability lies at the bottom of the vertical, exogenous, component of the currency. The consolidated government sector (the treasury and central bank) is at the top of the vertical chain because it is the sole issuer of currency and the transactions that the treasury and the central bank make with the non-government are able to alter the net system balance.

The middle section of the graph is occupied by the private (non-government) sector. It exchanges goods and services for the currency units of the state, pays taxes, and accumulates the residual (which is in an accounting sense the federal deficit spending) in the form of cash in circulation, reserves (bank balances held by the commercial banks at the central bank) or government (Treasury) bonds or securities (deposits; offered by the central bank).

The currency units used for the payment of taxes are consumed (destroyed) in the process of payment. Given the national government can issue paper currency units or accounting information at the central bank at will, tax payments do not provide the state with any additional capacity to spend.

The reason we take a consolidated approach to government in the first instance is because the two arms of government (treasury and central bank) have an impact on the stock of accumulated financial assets in the non-government sector and the composition of the assets.

The government deficit (treasury operation) determines the cumulative stock of financial assets in the private sector. Central bank decisions then determine the composition of this stock in terms of notes and coins (cash), bank reserves (clearing balances) and government bonds with one exception (foreign exchange transactions).

The point is that a central bank can at any time expand expand their balance sheets in the currency of issue in their nations. It certainly does not need to change its foreign assets to do so although it might for operational reasons to be explained.

So the fundamental proposition that the RBA needs “American dollars to Mint Australian Ones” is nonsensical and dead wrong.

We also quibble about the terminology. Minting is the manufacturing of coins for currency. In Australia, the Royal Australian Mint “is a prescribed agency within the Commonwealth Government portfolio of the Treasury and is the sole supplier of Australia’s circulating coinage”.

In terms of note issue, the “Reserve Bank Act 1959 confers on the Reserve Bank of Australia the responsibility for the production and issue, reissue and cancellation of Australia’s banknotes.”

Spurious Center reasoning

But the fundamental point is that at any time the RBA could, for example, accept paper from the Federal government or authorised deposit-taking institutions (private banks) and credit $A balances in the favour of the government or bank. The accounting transactions are trivial and do not require any offsetting transactions in foreign reserve assets, as is stated by the “Center for Geoeconomic Studies”.

Their argument also fails to present a reasonable understanding of what actually happened to the RBA’s Balance Sheet over the last several years despite presenting a graph purporting to be based on that Balance Sheet.

They claim to show that:

… when the … Australian central bank … expanded credit dramatically during the recent financial crisis their net foreign assets plummeted.

As if one required the other and without questioning causality or seeking to represent what really went on they conclude:

So it turns out that you do indeed need euros and (American) dollars to create … Australian dollars. A country that plows on creating credit without them eventually becomes a ward of the IMF.

You see the twist appearing at the end. Even by their own logic a central bank doesn’t need foreign reserves to create balances in its own currency but their assertion is that without some unspecified offsetting transaction in the foreign exchange market the nation would need IMF support.

The blog is not honest enough to map out their argument any more than that.

Before I examine what actually happened to the RBA Balance Sheet during the crisis this is what MMT would tell you about a central bank that created net financial assets in the currency of issue.

First, we define the monetary base as being comprised of:

- The currency (notes and coins) held by the public and issued by the government);

- The deposits that the commercial banks have with the central bank – the so-called reserves;

- The liabilities the central bank has to the non-bank financial intermediaries.

The term “base” is loaded because it is seen by the mainstream as the base on which banks lend from. Of-course bank lending is not reserve constrained so the term lacks meaning in this context.

There is no money multiplier – please read my blogs – Money multiplier and other myths and Money multiplier – missing feared dead – for more discussion about why there is no money multiplier.

Also the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – has further discussion on this point.

So central bank transactions with the non-government sector can change the monetary base. For example, suppose the national government is running a budget surplus, which results from the government spending less than it drains via taxation revenue from the non-government sector. This results in an overall withdrawal of net financial assets from the monetary system which reduces the monetary base.

But if the central bank then buys government debt from the non-government sector and creates bank reserves in the process (an open market operation) then the impact on the monetary base can be neutralised. From a MMT perspective this is a bank reserve operation which allows the central bank to effectively conduct its liquidity management tasks so that it can achieve its target interest rate.

Please read the suite of blogs – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 – for more discussion of these liquidity operations.

In the RBA Annual Report 2005 we read a very interesting account of how the central bank implements monetary policy:

Monetary policy decisions are implemented through operations that affect the supply of funds available to banks in the domestic market. The specific funds in question are those held by banks in their Exchange Settlement accounts at the Reserve Bank. These funds, known as Exchange Settlement (ES) funds, are the means by which banks settle their obligations with one another and with the Reserve Bank.

As these deposits earn interest at slightly below market rates, banks seek to hold only enough to meet their day-to-day settlement needs – in aggregate typically around $700-800 million. If the supply were to fall below this for any sustained period, individual banks would tend to increase the interest rate at which they are prepared to borrow in the money market to try to restore their holdings. Conversely, if supply rose excessively, banks would seek to dispose of the excess by reducing the rates at which they are willing to borrow and lend.

In other words, liquidity operations have to be conducted to ensure that the supply and demand for reserves meets the banks’ desired holdings. So the RBA tell us that “The domestic markets transactions used … to manage the supply of ES funds may be either outright purchases or sales of securities, or more usually repurchase agreements or ‘repos’, involving the purchase or sale of a security with an undertaking to reverse the transaction at a future agreed date and at an agreed price. Domestic operations may also be augmented with foreign exchange swaps”.

As we will see later, the increasing use of foreign exchange swaps and then the abandonment of them helps to explain the dynamics of the RBA’s Balance Sheet since the late 1990s.

What about foreign exchange transactions?

The external position of a nation impacts on the monetary base if there is official central bank foreign exchange transactions conducted by the central bank. A nation’s currency is demanded in foreign exchange markets to facilitate the purchase of its exports by foreigners; to pay interest, profits and dividends to residents who have foreign investments; and to facilitate foreign direct investment in local companies.

Conversely, a nation’s currency is supplied to foreign exchange markets to facilitate the purchase of imports from other countries; to pay interest, profits and dividends to foreign investors; and to facilitate lending to foreign companies.

Ordinarily, where there is a balance of payments deficit the demand for a nation’s currency in foreign exchange markets will be less than the supply of that currency and there will be downward pressure on the exchange parities. When there is a balance of payments surplus the demand for a nation’s currency in foreign exchange markets will be greater than the supply of that currency and there will be upward pressure on the exchange parities.

So exchange rate movements can arise from the real sector and the financial sectors with the latter increasingly dominating in the era of financialisation.

A floating exchange rate system allows these supply and demand imbalances in currencies to resolve themselves via exchange rate movements with no impact on the monetary base.

However, under a fixed exchange rate system, a country with an external deficit (supply of currency greater than demand) would face downward pressure on its parity and the central bank was committed to easing that quantity imbalance by conducting official foreign exchange transactions. So in this case it would buy its own currency in the foreign exchange markets by selling foreign currencies until the demand and supply of the local currency was equal and consistent with the fixed exchange rate being targetted.

These transactions would drain the local currency from the economy (the foreign exchange market is considered part of the monetary system) and so the monetary base would shrink.

If the nation had an external surplus (supply of currency less than demand) it would face upward pressure on its parity and the central bank had to sell its own currency in the foreign exchange markets by buying foreign currencies until the demand and supply of the local currency was equal and consistent with the fixed exchange rate being targetted.

These transactions would inject the local currency from the economy (the foreign exchange market is considered part of the monetary system) and so the monetary base would increase.

In a pure floating regime with no official central bank intervention, there is no change in the volume of a nation’s currency as a result of the foreign exchange transactions.

As an example, assume an exporting firm in Australia earns $USDs and seeks to convert them into $AUDs. It will sell them to a foreign exchange dealer who brokers a deal with a counterparty who desires to hold $USDs and already has $AUDs (perhaps an importing firm).

The exporting firm’s holdings of $AUDs rises as the counterparty’s holds fall. There is no change in the volume of AUDs on issue.

Clearly, things are different in a pure fixed exchange rate system as noted above. A floating exchange rate system thus does no hamper monetary or fiscal policy in the same way that monetary policy is forced to defend the parity in a fixed exchange rate system.

In reality, the central bank still conducts official foreign exchange transactions even if the currency mostly floats. So when the currency is weak (and the central bank fears an inflationary spike coming via increased import prices), it may intervene and buy foreign currency and vice versa when the currency is strong (and there is a fear that the competitiveness of the trading sector is compromised).

The RBA also manipulates its reserve assets (foreign currency and gold) on behalf of its clients. So from the 2010 RBA Annual Report we read:

The Reserve Bank carries out transactions in the foreign exchange market on a daily basis. The Bank operates in both the spot market and the market for foreign exchange swaps. Most of these transactions are undertaken on behalf of the Bank’s clients and are typically small by value. Some result from the day-to-day management of the Bank’s portfolio of foreign currency assets. Other larger but less frequent transactions arise from policy operations. These are mostly transactions undertaken to assist with the Bank’s management of domestic liquidity, and complement the Bank’s open market operations. On rare occasions, the Bank intervenes in the foreign exchange market. Intervention is only carried out to address disorderly market conditions or when the exchange rate is judged to be significantly mispriced …

he Reserve Bank provides foreign exchange services to its clients … the Bank’s largest client is the Australian Government. The Government purchases foreign currency from the Bank to meet a range of obligations, including defence expenditure, foreign aid and the costs of maintaining its diplomatic presence around the world. The Bank typically covers sales of foreign exchange to its clients directly from the market but can fund them temporarily from reserves if market conditions warrant this. In 2009/10, the Bank sold $7.3 billion of foreign currency to the Australian Government, which was covered in the market.

Recent developments in the RBA’s Balance Sheet

To further understand why the RBA’s Balance Sheet changes I thought some graphs might help given the “Center” used a graph (showing net domestic and net foreign assets) to make their spurious claims. The movements in net assets can be easily understood by just focusing on the asset structure of the RBA Balance Sheet.

The relevant data is available from – Reserve Bank of Australia – Table A1 Liabilities and Assets – Monthly. You can also find a lot of detail in –Open Market Operations and Foreign Exchange Transactions and Holdings of Official Reserve Assets.

This data along with a study of the Annual Reports will help you to understand what has been going on.

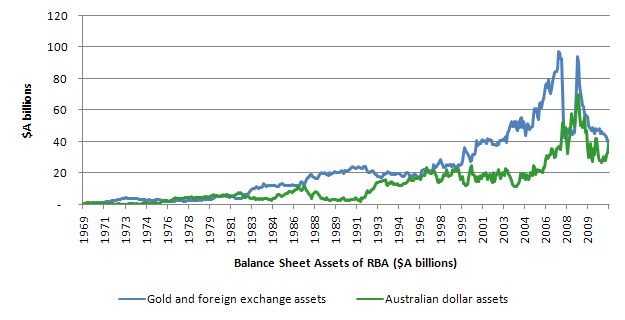

The first graph shows the movement in the Asset side of the RBA’s Balance Sheet since August 1969 to May 2011. The assets are divided into “Gold and foreign exchange” (so mostly foreign currency-denominated assets) and Australian dollar securities. The latter is composed of Australian Government bond holdings and other financial assets. The total assets also include small amounts (Loans and advances, Clearing Balances and Other items) which are small in volume and can be ignored.

The stand-out trend in this graph is the increase in foreign currency assets since about 1999 and the volatility around mid-2007. We will consider the second issue soon because it impacts on how we view the claims that motivated this blog.

But how do we explain the expansion of the foreign-currency assets from 1999 held by the RBA?

In 1996, the conservative government started running surpluses as part of its obsession with retiring all Commonwealth debt. This decision started to impact on the RBA’s liquidity management operations.

In the RBA Annual Report 2001 we read:

More recently, the challenges for market operations have been in adapting to the declining supply of Commonwealth Government securities (CGS) on issue, as the Government used budget surpluses and proceeds of privatisations to repay debt. Traditionally, market operations had been limited to transactions in CGS, either outright purchases and sales or repurchase agreements (repos as they are often called). While technically, domestic market operations could be carried out in any asset, the RBA had traditionally confined domestic operations to CGS because they carry no credit risk and the market for them was deep and liquid, facilitating the large transactions often involved in domestic market operations.

So an explicit recognition that Australian federal government debt is risk free meaning there is no solvency risk.

The RBA continued to explain their new strategy in the face of a declining stock of government paper.

However, with the supply of CGS in the market declining by more than a third since 1996, it has become necessary to broaden market operations to encompass new instruments. One such change was to use foreign exchange swaps more actively for domestic liquidity management. Foreign exchange swaps work similarly to repos, with the difference being that Australian dollars are exchanged for foreign currency rather than domestic securities. As with repos, the counterparties can agree the term of the swap to suit their particular needs. Use of these instruments began in a small way in the late 1980s, but has become much heavier in recent years.

… It should also be noted that, while the use of foreign exchange swaps increases the RBA’s holdings of foreign exchange, it has no effect on net foreign reserves, as the increased holdings of foreign exchange are matched with a commitment to sell foreign exchange at a pre-determined price and date. For the same reason, use of swaps has no effect on the exchange rate.

If you consult the data in Table 4 of the RBA statistics – Foreign Exchange Transactions and Holdings of Official Reserve Assets – you will see how significant these swaps became. The RBA could have just as easily paid a full market interest on the excess reserves and avoided dealing in the foreign exchange markets at all.

So whereas the typical repo will involve adding or subtracting Australian dollars from the banking sector reserves in exchange for domestic securities the foreign exchange swaps do the same thing by exchanging foreign currency. So the RBA exchanges “one currency for another with an agreement to reverse the transaction at an agreed exchange rate and on an agreed date”.

The RBA also responded to the decline in CGS by broadening the “the range of securities in which the Reserve Bank is prepared to deal” in its repos. The RBA started to collaterise repos in private bank bills and certificates of deposit.

But why did the RBA Balance Sheet expand so dramatically? The RBA Annual Report 2006 tells us the answer:

Over recent years two forces have been shaping the way the Reserve Bank conducts its operations. First, its balance sheet has expanded substantially, mainly because of deposits placed by the Australian Government from the proceeds of its budget surpluses. Over the past four years, the balance sheet has increased by more than 75 per cent, to over $100 billion, with the majority of the rise owing to larger Government deposits, including recently those of the Future Fund. Second, there has been a decline in outstandings of Commonwealth Government securities (CGS), the securities that had traditionally formed the staple of the Reserve Bank’s market operations. To accommodate these two forces, the Reserve Bank has broadened the range of domestic securities in which it is prepared to deal and made more use of foreign exchange operations to manage domestic liquidity.

The result has been a substantial change in the composition of the balance sheet. Compared with four years ago, holdings of CGS (including under repo) have halved, to around $7 billion, while holdings of other domestic securities have risen strongly. The largest rise in assets, however, has been in foreign exchange holdings. Including amounts held under swaps, holdings of foreign exchange have increased by about $30 billion over the period, accounting for about three-quarters of the expansion of the balance sheet. This has reduced the pressure on domestic securities markets resulting from the contraction in government debt.

The so-called Commonwealth Budget Surpluses were in fact diverted by the Federal government into its Future Fund. Please read my blog – The Futures Fund scandal – for more discussion on this point. So instead of spending on schools and hospitals the Government (via the Future Fund) deposited the cash in the RBA.

The RBA then offset that liability by investing mainly in “holdings of government securities and bank deposits in a range of foreign currencies”. The RBA accumulates US, Euro- and Japanese government bonds according to strict ratios etc.

So that explains why foreign currency assets grew so significantly prior to the crisis as part of the overall RBA Balance Sheet expansion.

It is also important to realise that changes in the Balance Sheet valuations may indicate actual transactions or valuation changes arising from exchange rate movements. The valuation impacts can be very dramatic in Australia given how volatile our exchange rate is at times. For example, in March 1985 the RBA conducted foreign exchange transactions of the order of minus $A374 million but valuation effects on its stock of reserves were of the order of $A390 million meaning that official reserves rose by $A16 million only.

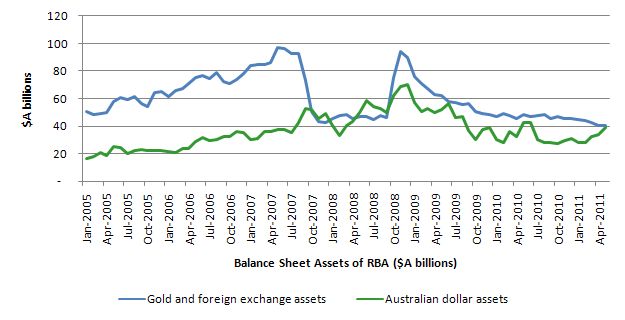

To focus on the crisis period more closely the following graph zeros in on the period January 2005 to April 2011. You can see what look like extraordinary movements in the foreign currency assets.

The RBA Annual Report 2008 tells us that:

For a number of years there had been a substantial increase in the size of the balance sheet, reflecting the increase in government deposits as a result of ongoing budget surpluses. In 2006, some of these deposits were transferred in name to the Future Fund upon its establishment, while remaining on deposit at the Reserve Bank. Since June 2007, deposits held by the Future Fund have fallen by around $40 billion as the Fund withdrew most of its deposits and invested the funds in a broader range of assets …

As these deposits, which are a liability of the Reserve Bank, were reduced, the Bank correspondingly ran down its asset holdings, primarily by reducing its holdings of foreign exchange held under swap. As noted in previous annual reports, the Bank had made extensive use of foreign exchange swaps in recent years to manage domestic liquidity as the balance sheet had grown.

That is, nothing at all to do with the measures it took to deal with the crisis some time later as is asserted in the spurious claim that to “Mint AUD” you need to have US dollars to sell.

In terms of the way the RBA handled the financial crisis, the 2009 Annual Report is helpful.

We read that the RBA:

… made a number of modifications to its market operations. These included:

– increasing the supply of ES balances;

– lengthening the term of its repos;

– conducting a larger share of its repos using private securities;

– widening the pool of securities eligible for use in repos;

– introducing a term deposit facility; and

– initiating a swap facility with the US Federal Reserve for institutions to receive US dollar funding.

I haven’t time today to analyse each of these operations in detail. They all had the effect of significantly expanding the RBA’s Balance Sheet (holdings of assets) during the second-half of 2008 including the holdings of foreign currency assets.

First, the RBA met the private banks’ demand for more reserves by increasing the supply (with the stroke of a computer keyboard). No foreign exchange transactions were (or would have been) required to facilitate this expansion of “$A liquidity”

Second, of the other initiatives, the RBA entered into an arrangement with the US Federal Reserve to ensure that there was an adequate supply of US dollars in the international system. The RBA swapped $A dollars for US dollars and then “on-lent the US dollars to banks operating in the local markets against the receipt from the counterparty of local currency assets”. The RBA explicitly “auctioned the US dollars obtained under the swap to its regular pool of domestic counterparties at terms of between one and three months” with “Australian dollar denominated securities” pledged “under a repo”.

As market conditions improved these arrangements diminished and the RBA Balance Sheet contracted. As the RBAs liabilities declined they were able to run down their corresponding assets.

Conclusion

I hope that sojourn through the RBA’s Balance Sheet – brief though it was – was useful in helping you put a few of the missing pieces about MMT together.

The RBA operates in a similar way to all central banks although remember Australia is a small, open economy and largely a price-taker on international markets which has particular challenges for monetary policy.

That is enough for today!

Cor,

I’m glad I didn’t try to respond to that blog on my own. I’m still missing so many pieces when it comes to central bank operations.

So the causality runs the opposite way. The central bank expands their balance sheet and then engages in foreign exchange swaps, etc to get the liquidity where it is needed in the real economy.

The foreign asset changes can be explained by international liquidity management operations and by valuation fluctuations caused by having to carry the foreign assets on the balance sheet in $A terms.

I’ll get this straight in my head eventually.

Austrians feel the need to view the Universe as having some central point around which all other points move. Hence their constant search for a natural base value of money, often (but not always) gold. I suspect if Austrians were interested in cosmology, they would still be claiming a geocentric universe as they tried to burn as heritics the neoliberals, who would be claiming a heliocentric universe.

Poor dears. However could they understand MMTers, strangers in a strange land who claim that everywhere and nowhere is the center all at once. It is all relative, they say, and merely depends upon which view you need at any time.

As a practical matter, even though there really is a Governor-General, when used in legislation like this ‘Governor-General’ really means ‘the PM and cabinet’.

I’m never able to read all the post. Too long.

I suggest to write a bit less. I think it’s important to summarize much more for increasing the number of readers.

cheers

Dario

Well you can only skip to the conclusion, but you’re not going to learn much that way.

I’m going to have to read that about 10 times but after the first reading it looks beautiful.

“Austrians feel the need to view the Universe as having some central point around which all other points move. Hence their constant search for a natural base value of money, often (but not always) gold. I suspect if Austrians were interested in cosmology, they would still be claiming a geocentric universe as they tried to burn as heritics the neoliberals, who would be claiming a heliocentric universe.”

Yeah, it’s actually a very primitive way of thinking. Copernicus would have laughed.

It does ensure one thing though: if you assume a world with such perfection, you’re likely to find monsters everywhere in the real world. I think this accounts for the Austrians’ vague but quite consistent apocalyticism.

Interesting post with lots to digest.

I don’t understand why the surpluses resulted in an expansion of the RBA balance sheet, though. Don’t surpluses just change the composition of liabilities on the CB balance sheet (decrease reserves, increase govt deposits)? I can see that this could lead to expansive monetary operations in order to maintain interest rate control – is that the idea?

Similarly, wouldn’t spending from the Future fund add to bank reserves like any other form of government spending, with no net change in CB liabilities overall? Why did this lead the CB to run down it’s assets? I feel like I’m missing something.

Paradigm,

Very nice questions.

Interesting points.

Not so straight forward if the Treasury and the Central Bank behave in funny ways such as the case here – in which the officials seem to treat surpluses as nest egg that needs to be preserved.

Lets assume that a Government runs into surpluses. One would expect it to pay down its debt – i.e., reduce its indebtedness and the Government deposit account at the central bank will have a balance close to zero.

It could also move the funds elsewhere by lending to the financial system in which case, funds move out of the central bank account. May not be a worthwile strategy but an option nontheless.

However the RBA didn’t do either of the two.

The Australian Treasury seemed to have believed that the surpluses are like nest egg. Now since the Government’s account is growing in size, banks would have been losing settlement balances continuously. They would then go into higher and higher overdraft position at the RBA. Or else, the RBA purchases securities in the open market.

Now the question is why the RBA decided to purchase foreign securities instead of Australian Government Bonds. I guess the public debt was very low and there were less government securities in the market hence the RBA decided to purchase foreign currencies.

PS: understood your “sawtooth”point (in another post).

Thanks for your reply, Ramanan. That’s pretty much what I suspected; Interesting that the Aus govt debt market was thinned out to the extent that the CB looked elsewhere to engage in its monetary operations. I’m guessing that there wasn’t an absolute shortage of govt debt in the market, but perhaps they didn’t want to unduly influence conditions in the secondary govt debt markets?

Don’t some countries with thin govt debt markets trade in CB debt securities as a means of conducting parallel monetary operations? I remember the idea being floated in the US by Bernanke a few years ago as a possible means of absorbing the evil “excess reserves” that were apparently going to create inflationary conditions over there.

BTW, do you have a useful reference for T-account transactions with the foreign sector? I’m trying to head around the balance sheet changes etc but can’t seem to find a decent source.

oops..”get my head around”

ParadigmS,

Even I thought there was no absolute shortage but just that the RBA didn’t want to influence the market. Perhaps a lot of holders of the government bonds may want to hold it to maturity.

Yes, ECB issues debt certificates – but the case is opposite to here. Even the Fed was planning to issue Fed certificates or some such thing. In other cases, in nations which engage in a lot of foreign exchange purchases, the extra settlement balances created are eliminated by issuing central bank bills. In the case of Australia, there was no need because it seems fx purchases were driven by government deposits.

There is no single source for T-account transactions with the foreign sector. You could start with the IMF’s Balance of Payments Manual. v6 is the latest version. Its also called BPM6.

Other refs:

Balance Of Payments And International Investment Position, Australia – Concepts, Sources And Methods

Balance Of Payments Compilation Guide, IMF

Balance Of Payments Textbook, IMF

Canada’s Balance Of International Payments And International Investment Position

United Kingdom – Balance Of Payment – The Pink Book

(don’t have links).

R, thanks, I’ll look into those. So much to learn!

Paradigm,

Lot of it is technicalities – but becomes interesting after a while. In the Australian guide, section 2.1 is a table which shows transactions in the current account and financial account and how the latter feeds into the stocks of assets and liabilities. Plus revaluations. Very nice table.