I have received several E-mails over the last few weeks that suggest that the economics…

Technocrats move over, we need to read some books

I was reading the recently published (June 11, 2012) – CBI Education and Skills Survey 2012 – from the Confederation of British Industry today. A day after the Report was published, the British Office of National Statistics released the latest (April 2012) – Index of Production – data which shows that “the seasonally adjusted Index of Production fell by 1.0 per cent” over the 12 months to April 2012 and that in the last month the “seasonally adjusted Index of Manufacturing fell by 0.7 per cent”. That is a large collapse. Since 2008, British production has slumped by 10 per cent overall even though the currency has depreciated by around 20 per cent against the Euro over the last 5 years. Earlier today I saw news footage of ignorant males (mostly) beating each other up over a soccer game in Warsaw. And in recent national elections, polarisation towards the extremes is evident. And all the while, technocrats that dominate organisations such as the IMF and the ECB are, inexorably, pushing economies into even more dire situations that we could have imagined four years ago, when the neo-liberal bubble burst. And in my own sector (higher education) the buzz is STEM and technocrats are using that buzz agenda to pursue strategies that will diminish our futures irrevocably. All these events, outcomes, strategies etc are related and cry out for a major shift in thinking by governments and educational institutions.

The CBI Report says that the majority of surveyed businesses identified as a leading issue to be progressed the “business relevance of vocational qualifications”.

A majority also wanted more government handouts to subsidise on-the-job training – again blurring the responsibilities of government and corporate sector activity to advance the narrow sectoral interests of the latter.

73 per cent of respondents said that “the need to provide businesses with the skills they require is the single most important reason to raise standards in schools.

71 per cent said that they wanted 14-19 year olds attending schools and colleges that are “prioritising development of employability skills”.

First, economists make a distinction between general and specific skills. The former are those that deliver broad social returns beyond the benefits they provide the individual recipient. That is, spending on an individual to gain general skills (such as literacy, numeracy, broader understandings of arts and literature) create externalities, which even the mainstream economists acknowledge and agree that these should be the object of government spending to ensure that there is enough investment in these skills.

Because the social returns outstrip the private returns arising from general skill development a private market would under-provide such skills and we would all be worse off.

As a result, there is broad acceptance that public education to the end of secondary school is a sound strategy even though the neo-liberals continually propose cuts in these areas when they are trying to come up with ways to cut government spending.

Specific skills (for example, certain firm-specific work practices, technologies etc) tend to deliver lower social returns and higher (relative) private returns and so the case for public provision declines. Given that firms and their workers will tend to reap the benefits of this skill development there is a strong case that government should not be subsidising profits to entice firms to provide training. Vocational training falls into this category.

The majority of respondents wanted an increased involvement of business in school affairs – including school governance, and “schemes … to promote subject study” (so-called STEM Ambassadors are noted as a positive development).

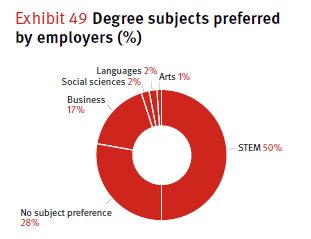

Then we came to STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths). Half of the employers claimed they prefer their recruits to have STEM higher education paths with Business (17 per cent) the next preferred option. Employers “are looking out for employability skills first and foremost”. The following graphic is particularly scary and is reproduced from the CBI Report’s Exhibit 49:

The preferences expressed in the Pie-Chart are wide-spread and have influenced governments and higher education institutions. Increasingly, funding models between government and higher education institutions and those that determine allocations within higher education institutions are being driven by the STEM mania.

The humanities (Arts degrees) are under increasing threat from the application of Key Performance Indicators (the KPI mania) that are biased towards STEM-type disciplines and are distinctively disadvantageous for the humanities.

I have yet to see a KPI that attempts to evaluate the value of the development of democratic ideals or historical understanding or the beauty of the word or sound.

These pressures bring into relief questions about what role should education play? This is not a new debate.

Capitalism has always tried to embrace the educational system as a tool for its own advancement but social democratic movements have, in varying ways, resisted the sheer instrumentalism that the business sector seeks.

The book by Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis – Schooling in Capitalist America – [Full Reference: Bowles, S. and Gintis, H. (1976) Schooling in Capitalist America, New York: Basic Books] – argued that (page 11):

… by imparting technical and social skills and appropriate motivations, education increases the productive capacity of workers. On the other hand, education helps defuse and depoliticize the potentially explosive class relations of the production process, and thus serves to perpetuate the social, political, and economic conditions through which a portion of the product of labor is exporpriated in the form of profits.

In other words, the education system is continually pressured by the dominant elites to act as a breeder for “capitalist values” and to reproduce the hierarchical and undemocratic social relationships that are required to keep the workers at bay and expand the interests of capital.

So there is an overlap between the way education is organised and the way the workplace is organised. It is not as simple as that but that is the idea they wish to present. There is considerable merit in that conceptualisation.

The neo-liberal era has seen the corporate instrumentalism advanced to new heights.

When governments abandoned responsibility for full employment (that is, using fiscal and monetary policy to ensure that there would be enough jobs and working hours to satisfy the preferences of the willing workforce) and replaced it with the diminished goal of full employability (that is, the goal of making workers ready for work) – they also narrowed the vision of our educational sector.

Schooling system administrators and a new breed of university managers took up the neo-liberal agenda with relish, not the least because their own pay sky-rocketed and the previous relativities within the academic hierarchy between the staff who taught and researched and those that took management roles lost all sense of proportion.

Instead of rebelling and making the funding cuts and the increased demand for STEM type activity a political issue – which in Australia at least would have seen the government back down – the higher education managers embraced the new agenda without fail.

Increasingly, the employability agenda invaded curriculum and higher education institutions progressive moved towards vocation and away from education. The distinction between education and training is being blurred if not lost.

As Martha Nussbaum argues in her 2010 book – Not For Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities – we:

We are in the midst of a crisis of massive proportions and grave global significance … I mean a crisis that goes largely unnoticed, like a cancer; a crisis that is likely to be, in the long run, far more damaging to the future of democratic self government: a worldwide crisis in education.

Radical changes are occurring in what democratic societies teach the young, and these changes have not been well thought through. Thirsty for national profit, nations, and their systems of education, are heedlessly discarding skills that are needed to keep democracies alive. If this trend continues, nations all over the world will soon be producing generations of useful machines, rather than complete citizens who can think for themselves, criticize tradition, and understand the significance of another person’s sufferings and achievements. The future of the world’s democracies hangs in the balance.

What are these radical changes? The humanities and the arts are being cut away, in both primary/secondary and college/university education, in virtually every nation of the world. Seen by policy makers as useless frills, at a time when nations must cut away all useless things in order to stay competitive in the global market, they are rapidly losing their place in curricula, and also in the minds and hearts of parents and children. Indeed, what we might call the humanistic aspects of science and social science- the imaginative, creative aspect, and the aspect of rigorous critical thought-are also losing ground as nations prefer to pursue short term profit by the cultivation of the useful and highly applied skills suited to profit making.

She lists many examples of these trends.

So we are increasingly treating education “as though its primary goal were to teach students to be economically productive rather than to think critically and become knowledgeable and empathetic citizens”.

It is not just the humanities. In my own discipline, there have been major pressures to eliminate the “social science” aspects of the course of study (including studies of comparitive systems; economic history; history of economic thought; social economics and such) in favour of a narrow “business economics” agenda.

I began my professional academic life within an Economics Department, which was part of an Economics and Politics faculty (moulded on the old ECOPs tradition)/ I then moved through various structures such as Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences/Economics Departments, into an Economics and Commerce Faculty/Economics Department which was then re-named a Business Faculty with the Department disappearing altogether into a School of Business and much of the social science content of the program eliminated (along with the Economics Degree). Fortunately, I had moved into my research centre (outside of the Faculty structure) prior to that last machination.

These trends have occurred everywhere. At a time when the world is going through the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, universities are downsizing or eliminating economics as a field of study in favour of business vocation.

Do you see Human Resource Management, Marketing, International Business and all the rest of them on the front pages of the newspapers and leading our news bulletins each day? I don’t. I see economics.

I also see behaviour from our political classes and the media in general that cry out for historical insight and broader understandings of human society – the knowledge and wisdom that a humanities education provides.

Instead of deep understandings of the mistakes made in the past, I see statements from Bundesbank-type officials prioritised, erroneous claims by mainstream economists in the service of the corporate sector prioritised.

And the results of the repetitive policy errors is entrenched high unemployment and increased social dislocation and a generation of youth that have no real prospects and think it is a good look to make the headlines beating each other up over a sporting event.

I considered some of these points in these blogs – I feel good knowing there are libraries full of books and Education – a vehicle for class division – and they make good background reading for this blog.

The way in which all the events I cited in the introduction are linked is that the neo-liberal era has successfully imposed a very narrow conception of value in relation to our consideration of human activity and endeavour. We have been bullied into thinking that value equals private profit and that public life has to fit this conception.

We have been forced into believing that a budget outlay in some document, or a ratio in another is important while at the same time we blithely see 50 per cent of 15-24 year olds in an indefinite state of unemployment – the buffer rising as nations are pressured into obeying even stricter (but equally irrelevant) financial ratios.

In doing so we severely diminish the quality of life. The attack on the humanities is an expression of this trend. The pursuit of fiscal constraints in the face of a worsening crisis of insufficient aggregate demand is another expression.

The manifestations are lost production, social instability, polarisation towards deeply irrational political perspectives, and moves to undermine and usurp democratic processes.

The pressure on universities to bow to the STEM god and undermine humanities and social sciences that cannot be directly related to the corporate profit margin and the rising unemployment and lost production can be traced back to the lies that we are told about the fiscal constraints.

That is why when I write about economics I am also seeking to provide arguments for those who seek to defend all the areas of our society and life that are under siege from the neo-liberal KPI machine – where the fiscal rules and financial ratios are in the same class of largely irrelevant KPIs.

It is clear that academics should be rebelling against public policy benchmarks based on “private market calculus”. Education is broad, whereas the corporate sector is narrow.

I remind readers of the great American author, Harry Braverman who clearly saw (in the early 1970s) the way that neo-liberal would impose its constructs on us and seek to apply them to all aspects of human activity.

In his – Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century (New York, Monthly Review Press, 1974) – Braverman wrote (pages 170-71):

Thus, after a million years of labour, during which humans created not only a complex social culture but in a very real sense created themselves as well, the very cultural-biological trait upon which this entire evolution is founded has been brought, within the last two hundred years, to a crisis, a crisis which Marcuse aptly calls the threat of a “catastrophe of the human essence”. The unity of thought and action, conception and execution, hand and mind which capitalism threatened from its beginnings, is now attacked by a systematic dissolution employing all the resources of science and the various engineering disciplines based upon it. The subjective factor of the labour process is removed to a place among its inanimate objective factors. To the materials and instruments of production are added a “labour force”, another “factor of production”, and the process is henceforth carried on by management as the sole subjective element.

And progressively, these “labour processes” (market-values) subsume our whole lives – sport, leisure, learning, family – the lot. Everything becomes a capitalist surplus-creating process.

If we judge all human endeavour and activity by whether they are of value in a sense that we judge private profit making then we will limit our potential and our happiness.

One of the bulwarks against this descent into a narrow dog-eat-dog (but the richer dogs ensure they get their subsidies from the public trough before anyone else) trend are the humanities and critical thinking.

I would argue that understanding intellectual developments such as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is another bulwark. We are not poets and artists and men and women of the classic literature. We are not philosophers who sort out the logic from the cant.

But MMT is an essential aspect of the progressive defence against this descent into the slime.

The other issue is that once we accept these funding constraints and gear education towards STEM disciplines, it becomes obvious that we have to choose the latter over the humanities and other “non-earning” disciplines.

But that choice is based on a series of false premises that MMT exposes.

It is clear that the pressures that are now placed on universities to cut areas of education that don’t perform well under the biased KPIs are false pressures when we appreciate that there is no intrinsic financial constraint that has to be satisfied.

Governments should ensure the aggregate spending growth – which government spending is one part – is consistent with the real capacity of the economy to produce (that is, there are real resource constraints).

Which means that if a nation is running up against its inflation barrier then political choices have to be made. But I would rather limit, say, the mining industry and free resources and spending for education than the other way around.

As it stands, however, the neo-liberal era has been marked by the persistent slack (underutilised resources) that it has created.

Martha Nussbaum writes:

I do not at all deny that science and social science, particularly economics, are also crucial to the education of citizens. But nobody is suggesting leaving these studies behind. I focus, then, on what is both precious and profoundly endangered … The national interest of any modern democracy requires a strong economy and a flourishing business culture … this economic interest, too, requires us to draw on the humanities and arts, in order to promote a climate of responsible and watchful stewardship and a culture of creative innovation. Thus we are not forced to choose between a form of education that promotes profit and a form of education that promotes good citizenship. A flourishing economy requires the same skills that support citizenship, and thus the proponents of what I shall call “education for profit,” or (to put it more comprehensively) “education for economic growth,” have adopted an impoverished conception of what is required to meet their own goal.

This argument, however, ought to be subservient to the argument concerning the stability of democratic institutions, since a strong economy is a means to human ends, not an end in itself. Most of us would not choose to live in a prosperous nation that had ceased to be democratic. Moreover, although it is clear that a strong business culture requires some people who are imaginative and critical, it is not clear that it requires all people in a nation to gain these skills.

I also agree that developing scientific knowledge is necessary to advance productivity. But I see productivity in broader terms that that which a corporate firm would calculate (based on their private costs and returns).

The reason we promoted the humanities in the post Second World War period were also the same reasons we demanded our governments maintain full employment.

We wanted to promote strong and vibrant democracies and social inclusion. We thought that if people were well-educated (as opposed to well-trained) then social stability would be enhanced and there would be less scope for extremist views to gain traction.

But neo-liberalism is an extremist viewpoint which has managed to make itself appear to be a consensual body of ideas and those who are antagonistic to them are characterised in various pejorative ways – Keynesian dinosaurs; idiots, martians, communists, etc All terms that I have been called over my career, which unfortunately has overlapped almost completely with the neo-liberal dark age.

The point is that STEM disciplines need promotion along with the humanities and non-business areas of the social sciences. Moving resources into education and way from other environmentally damaging pursuits is sensible.

Once we get over the mythical governments-will-run-out-of-money lies then we have encourage development in both the technical sides of learning and the broader areas.

Knowing what is possible (technological limits etc) is not the same thing as knowing what is the best path to follow. Engineering might tell us about the latter but the humanities helps us create frameworks to make better choices about policy paths.

Conclusion

This blog is unfinished in the sense that I am working on a book canvassing these themes. The message is the same – the neo-liberals have persuaded us that national governments have financial constraints and that every activity has to be evaluated within the framework of private calculus that a corporate entity aiming to pursue value for their private owners would use.

This framework is already flawed by the existence of external effects (to the transaction) which means that the private market over-allocates resources when social costs are greater than the social benefits and under-allocates resources to this activity when social costs less than the social benefits.

But beyond that is a sense that the framework has little relevance to deeper meaning and the sort of qualities which bind us as humans – to ourselves, into families, into communities, and as nations.

The residual damage of the neo-liberal approach extends well beyond the huge economic losses it imposes on us in the form of persistently high unemployment and underemployment. The material poverty that it has inflicted on cohorts in our societies is one thing. But it is also imposing a poverty on all of us by diminishing our concept of knowledge and forcing us to appraise everything as if it should be “profitable”.

And all because we believe that there is a fiscal crisis. That bit of make believe is what I have tried to to address and refute over my career. I have not been very successful to date!

Now it is time to tune into Europe – another day, another bailout package, a further step into the slime.

That is enough for today!

“Earlier today I saw news footage of ignorant males (mostly) beating each other up over a soccer game in Warsaw. And in recent national elections, polarisation towards the extremes is evident.”

These people are mostly “ordinary garden-variety” fascists (they describe themselves as “true patriots” and people like me as “Polish-speaking” as opposed to “Polish”). It is true that the majority of hooligans are not intellectuals but they are not ignorant in terms of lack of education – they have been thoroughly “educated” – brainwashed into believing that Russia is their enemy which assassinated the previous President of Poland, etc. (on the Russian side the attitude is somewhat similar but these were Polish who started the riot).

These who pull the strings have academic degrees in humanities:

Jaroslaw Kaczynski (the twin-brother of the deceased President) – PhD in Law

Antoni Macierewicz – Master of Arts in History, unfinished PhD

Father Tadeusz Rydzyk – PhD in Theology.

I can go on … probably a waste of time. I am so happy that I opted out from that mess and my kids are now NOT how to put it… “Polish-Speaking”.

I fully agree with the “effects of applied neoliberalism” part of the analysis. This pushed a lot of young people into the arms of the religious fanatics and extremists.

Something that seriously bothered me in the lead up to our election last year in New Zealand was a construction going around comparing the educational backgrounds of the two most likely candidates for Prime Minister. Namely, one had an unspecified arts degree, while the other had a finance one.

Except that “arts” isn’t just literature and art history and whatever else people think of when they hear it and immediately mentally dismiss the person to a future in fast food. It covers both history and social policy, for starters, and personally I’d FAR rather live in a country where the Prime Minister had a history or social policy education than a finance one. Coincidentally I actually am now studying social policy and it’s incredibly illuminating, with even the introductory class giving me huge insight into politics that I never had before. Teaching even a fraction of this sort of thing in high school would lead to a much more engaged population, and unfortunately a good part of me suspects that that’s exactly what the right doesn’t want.

Hi Bill, great article I enjoy reading your blog every day and having a go at the quiz on the weekends. I have noticed that you haven’t posted a song lately which captures the mood or theme of your articles. So today I thought I would provide you with a song…:-)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EKFTtYx2OHc

I suspect that the “technocrats” you talk about do not know the meaning of “technology”.

Great post. My understanding is that in the ’50s and ’60s there was not the kind of anxiety over what a person majored in while at university as there is today, as there were many more jobs available and employers tended to be more willing to choose a more diverse array of people and train them on the job.

And of course, the world didn’t collapse because of this state of affairs, so it is possible that we can recreate this kind of environment again.

STEM will not solve unemployment, assuming that unemployment is still regarded as a problem by our elites.

It seems they would change our colleges into trade schools if they could. Except for their own children, no doubt.

Off topic, but excellent: What are the bankers up to? They really do want it all.

That’s capitalism for you. The tendency is to monetize absolutely everything–commerce settles on every branch, as Blake predicted. Lockean private property ideas along with the personhood of corporations means that ownership is increasingly concentrated by finance capital. It all amounts to turning humanity into a vast ant heap. Since money is counted, it turns every value away from the domain of quality (which only human intelligence and sensibility can evaluate properly) towards the pole of pure quantity, which is the domain of the machine and of digital culture. This tendency lays hold of everything and drains it of all qualitative significance into order to integrate it into its domain of quantity, money, profit. So of course, STEM-trained humans are the fittest for this enterprise of dehumanization.

I wholeheartedly agree with the notion that “higher” education is broken. However, having the questionable honour of obtaining an M.A. degree, I would say that the humanities/social sciences are part of the problem. I simply do not see the value of them. Although my own experience is anecdotal, I must say that the program was more or less pure nonsense: not only the promotion of practical skills was missing, so was the old idea of “cultivation of the intellect”. Based on my experience, my general advice would be this: if you would like to educate yourself, go to the library.

Now, I don’t think that higher education should be about practical skills, we have vocational schools and training centres for that. (And if businesses want certain specific skills, then let them arrange the training. The society – be it tax or government funded – has no obligation to serve the narrow needs of private interests.) I do think, however, that the “cultivation of the intellect” should be the essential content of higher education. And this I understand as science or the general scientific approach, its methods included. Again, the methodology part was non-existent. Seriously, what is the purpose of obtaining a master´s degree (in anything), when even simple statistics is a mystery, or if logic is something that happens elsewhere?

Nor can I see how democracy can be or has been benefiting from the humanities/social sciences – after all many of those who received such “education” during the past are today’s decision makers and voters; where are the results? The people I know who are critical of the present (and past) system have such opinion’s due to their own personal experience with the “western bliss” – or the former socialist equivalent – not because of the received education. Furthermore, if the link between democracy and education is considered as one of moral values – or something similar – then the question is, how do we know the teacher/lecturer/professor possesses the “correct” or “right” values. And if the values are something one should reach by himself (with one’s own cultivated intellect), then I see no reason why, say, a physics student or mathematician should be any less capable to do so.

Our survival and material well-being is a technical question. These are better answered with natural sciences (in the broad sense). On the other hand, we need to realise and think – as a society – what values are important and where we want to go. But here the humanities/social sciences have not – in my opinion – managed to give any better advice than natural sciences. Yet obviously there must be something in addition to mere securing the necessities of life. That can be – and has been in the past – achieved outside “higher education”. Be it music, art, social critique, etc., we don’t need universities for that…

University managers are indeed pursuing the employability agenda but I do not believe the academics who must design the courses are paying much more than lip service to this.

Also I think the focus on STEM in the UK actually has little to do with the needs of the likes of the CBI but is more a reflection that university funding models tend to work against these subjects. Needs of industry have been used by the academics and professional bodies involved in STEM to justify enhanced funding in these subjects. At least in the past the idea of STEM has been a measure of the weakness of some of these subjects (chemistry and physics in particular).

I would very much doubt whether STEM subjects have really participated in the large increase in UK graduate numbers of the past 20 years. In my view it is not a STEM versus the others but rather how subject areas within the arts and humanities compete amongst themselves.

Nigel

My formal education and my professional life were in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics, but I have opened many books outside those areas and spent time doing other things unprofessionally, such as playing music. However, when I look at books and listen to people talking on subjects such as philosophy and economics, with some exceptions, I find a lack of rigour which is quite disconcerting.

I suppose the reason I am here is that MMT seems to provide a good basis for the fundamentals of economics but I have many questions which are unanswered so far and I don’t know where to turn. Some economics books, for example one I read recently by Graziani, seem to be on the right track but are like travel books: they just give a fleeting glance at the subject as they pass by.

As long as I can remember, employers have complained that universities don’t provide graduates with the appropriate skills and universities claim that their job is just to teach students to think. Neither is completely true.

We are often told that we should be educating students in some area and we are not. Often there is insufficient demand by employers in that area and it’s hard to get a good job. Where there is demand by employers, students will be attracted to those areas. Since university funding is largely driven by student demand, those areas develop. In these cases, the main problem is the time lag between demand and supply.

The idea of an employment guarantee is good. However the implementation of that policy is not easy. It’s too easy for it to become a work for the dole program.

@Tony

If you have questions then just ask. I think you’ll find the readers here more than willing to discuss them.

Interesting how the results of the employer survey, with their Gadgrind like empahasis on teaching ‘facts’, contrasts with well publicised comments by the late Steve Jobs on how important he thought his liberal arts education was to his development of apple.

GP said: Lockean private property ideas along with the personhood of corporations means that ownership is increasingly concentrated by finance capital.

Hi GP can you use common language so I can follow this please. I can understand the rest of your comments.

Perhaps if people had to live in the same community that is affected by a their decisions at work they would be influenced by the environment they live in. A “village” would not put up with a money-lender taking home 20 times the average village wage. A village would not put up with policy failure on a repetitive basis. A “village” would not allow an individual to profit in billions from selling minerals mined in the hill behind the “village”. The clever and smart would be revered for their contribution to village life and this would be their reward. Those blessed with wonderful memories would study to benefit the community not their pockets. Tricking the have-nots into believing they too could share in what the haves enjoy by simply borrowing from the haves to buy the haves lifestyle is a trick with a sunset. The so-called safety nets have become golden handcuffs that will break once austerity destroys the net. The current winner takes all society is a dismal failure and will end in the have-nots taking what the haves flaunt. Cheers Punchy

‘They know the price of everything and the value of nothing.’

Thanks Bill for another educational and thought provoking blog on this important subject. Thanks also Punchy for your village analogy. Chris from NZ said: ‘Teaching even a fraction of this sort of thing in high school would lead to a much more engaged population’. There is of course a limit to the knowledge and understanding that can be imparted, especially at high school level, but at least a seed can be planted. Along the way that seed might lie dormant or develop in the wrong direction e.g. with neo-liberal blinkers, but there is a chance that it might finally blossom in understanding. Enough of the seed/flower metaphors.

Here in the UK we face such an uphill struggle to recover. In the late 70s I could study Economic and Public Affairs at a comprehensive school and then Economics and Politics at University in Thatcher’s Britain. I’m also interested in history, geography and yes, science. Now, the equivalent school time would be on Business Studies, with Economics offered if you’re lucky post 16. I have an idea of who teaches it – Business Studies teachers.