Last night, the Federal Government brought down the – 2013-14 Budget – claiming it was a responsible response to the circumstances it faced (declining world growth, declining terms of trade and persistently high exchange rate) and that it emphasised growth and jobs. Neither claim is remotely correct. It is a pro-cyclical budget – that is,…

The Fantasy Budget 2013-14

This is my Fantasy Budget 2013-14, which will be part of Crikey’s Budget coverage leading up to the delivery of the Federal Budget on May 14, 2013. This blog is relatively short and more or less within the constraints I was given with respect to words. I have added a section on the sectoral balances for clarity and some more detail about cuts.

The complete suite of Fantasy Budget blogs are as follows:

- The indecent inconsistency of the neo-liberals

- Australia output gap – not close to full capacity

- Daily macroeconomic income losses from unemployment

- The Australian labour market – 815 thousand jobs from full employment

- What is a Job Guarantee?

- Investing in a Job Guarantee – how much?

- MMT Budgetary Principles

- The Fantasy Budget 2013-14

The Australian government has a problem – the budget deficit is too small. How do I know that? There are 13.9 per cent of available labour resources idle and the current output shortfall from recent trends is around 4 per cent or $60 billion.

There is nothing intrinsically good or bad about any specific budget outcome. The outcome has to be related to the economic circumstances rather than to some pre-conceived notions that higher deficits are bad and surpluses are good.

It is not the government’s role to run deficits or surpluses. Government should aim to maximise the potential of all people so they can live rewarding lives and contribute to the well being of society and the planet.

An essential element of this public purpose goal is to ensure that any one who wants to work has a job and if unable to work, for whatever reason, has adequate income support so they are not alienated and socially-excluded.

The No.1 priority is not to balance the budget but to get nearly two million people back to working the hours they desire.

The achievement of that goal is constrained only by real resource availability. The Australian government cannot run out of money. The government budget is not like a household budget. It issues the Australian dollar, which we use. It can purchase whatever is for sale in Australian dollars, including the idle labour. Of-course, that doesn’t mean the government should spend willy-nilly.

The risk of excessive deficits is inflation, not insolvency. This risk arises when the capacity of the economy to produce real goods and services is outstripped by nominal spending growth. Australia is a long way from that situation. Inflation is subdued and falling.

So what size should the deficit be?

The government claims we are growing on trend and close to full employment. But even the OECD estimates the output gap to be around 2 per cent at present ($30 billion).

A closer examination would suggest the current departure from trend output growth is around $60 billion or 3.9 per cent. The gap is widening as the economy slows under the strain of declining terms of trade, overvalued dollar and fiscal austerity.

This large degree of slack is also mirrored in poor labour market performance.

The ABS estimates that there are 13.9 per cent of available workers not working (670 thousand unemployed, 869 thousand underemployed and around 150 thousand workers who want to work but are no longer actively seeking work due to lack of employment growth).

Mass labour wastage of this magnitude arises because there is insufficient spending in the economy. Trying to pursue budget surpluses only makes the problem worse.

The equivalent underutilisation figure for teenagers is 39.4 per cent. The longer-run consequences of this teenage “lock out” will be very damaging. While the ageing society debate has been represented as a fiscal issue, the real issue is whether the future workforce will be productive enough to support the growing proportion of dependents.

Creating huge pools of underutilised labour as a consequence of an obsession with surpluses will reduce future productivity and living standards.

The preferred budget deficit for 2013-14 should be around $70 billion or 4.5 per cent of GDP. This fiscal shift from an estimated deficit of around $20 billion in 2012-13, combined with a conservative estimate of the expenditure multiplier, would see the growth gap largely closed.

From another angle, the 2013-14 Current Account deficit will be around $70 billion (4.4 per cent of GDP). Who will fill that growing spending drain to ensure the national economy moves back towards trend? With the private sector intent on moderation, there is only one sector left – the government.

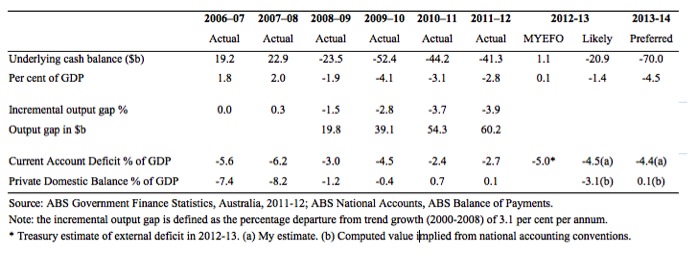

Table 1 Australian budget detail and forecasts

The data in the Table shows that in the pre-crisis credit binge, the private sector was running constant and growing deficits, which fuelled the growth that allowed the government to achieve its surpluses. The consequence was the unsustainable rise in private debt levels. It was a very atypical period in our history.

The private sector has now reverted to more typical historical saving behaviour as it tries to reduce its debt levels. As a consequence, private demand is not likely to drive strong growth in the coming years.

With a CAD of around 4.4 per cent of GDP, the budget deficit has to exceed that for the private domestic sector to save overall. The private sector will resist building up future deficits and an inadequately sized government deficit will lead growth to falter further and even higher unemployment.

That is the situation the government faces. If it doesn’t choose to expand now the economy will contract further. Moreover, given it doesn’t control the final budget outcome, its tax take will continue to wallow and it won’t achieve its surplus ambition anyway.

Checking policy consistency with basic accounting

Consider the national accounting identity for the three sectoral balances:

(S-I) ≡ (G-T) + (X-M)

Total private domestic savings (S) is equal to private domestic investment (I) plus the public deficit (spending, G, minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)), where net exports represent the net savings of non-residents. Thus, when an external deficit (X-M < 0) and a public surplus (G-T < 0) coincide, there must be an overall private domestic deficit. Excessive private spending can persist for a time under these conditions, using the net savings of the external sector, but eventually the increasing indebtedness becomes unsustainable. The sectoral balances framework allows us to understand the interaction between fiscal policy and private sector indebtedness. In a modern monetary economy where the government issues its own currency, it follows as a matter of national accounting that the sovereign government deficit (surplus) equals the non-government surplus (deficit). The failure to recognise this relationship is the major oversight of neo-liberal analysis. In aggregate, there can be no net savings of financial assets of the non-government sector without cumulative government deficit spending.

Government (via deficits) is the only entity that can provide the non-government sector with net financial assets (net savings), and thereby simultaneously accommodate any net desire to save in the unit of account, and hence eliminate unemployment.

Additionally, and contrary to neo-liberal rhetoric, the systematic pursuit of government budget surpluses is necessarily manifested as systematic declines in non-government sector savings.

If there is an external deficit (current account) and the government sector is running surpluses, the only way that the economy can continue to grow is for the private domestic sector to undertake increasing levels of indebtedness.

The deteriorating debt-to-income ratios that result will eventually see the system succumb to ongoing, demand-draining fiscal drag, through a slow-down in real activity.

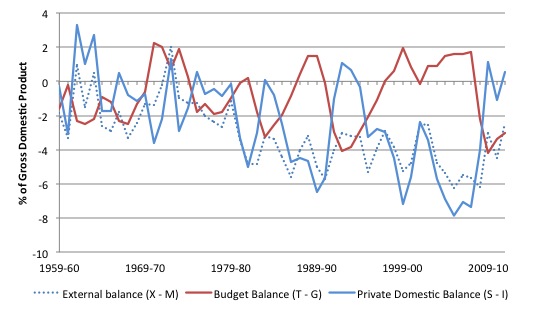

Figure 1 shows the sectoral balances for Australia for the period 1959-60 to 2011-12 as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). The external deficit has increased slightly over time, and fluctuates around the commodity price cycle.

Accordingly, the dramatic shift from budget deficits to surpluses from the mid-90s onwards has been mirrored by a corresponding rise in private sector indebtedness, as the private domestic sector started to dis-save overall (i.e. to spend more than it was earning).

Figure 1 Sectoral balances, Australia, 1959-60 to 2011-12; per cent of GDP

Source: RBA Bulletin database and Commonwealth of Australia Budget Paper No.1.

The Australian government was only able to run surpluses between 1996 and 2007 because the credit binge of the private domestic sector produced the growth that maintained spending growth. But this was an unsustainable growth strategy, because eventually the build-up of private debt became precarious.

As the crisis hit, households and firms started to reduce their debt exposure and adopt more typical saving patterns (e.g. household saving went from zero to around 10 per cent of disposable income).

The facts are inescapable. The neo-liberal period of public surpluses and private deficits was atypical for Australia. Similar trends occurred in most advanced nations over this period.

The sectoral balances show us that, when the private sector is deleveraging and a nation has an external deficit (of any size), then growth can only continue if there are budget deficits. That is the norm for most nations.

That is exactly the position that Australia is in at present and will remain in for the foreseeable future. The imperative is to ensure the deficit is big enough to accommodate the demand-draining behaviour of the other macroeconomic sectors.

What should be done?

Budgetary design is not just about eliminating the overall spending gap. The composition of spending and taxation also should achieve desirable goals.

As the first step to restoring full employment, the national government should introduce an open-ended public employment program – a Job Guarantee – that offers a job at a living (minimum) wage to anyone who wants to work but cannot find employment.

That would cost around $22 billion per annum in the first instance and reduce the unemployment rate to 2 per cent and create some 594.3 thousand jobs (around 70 thousand in the private sector). As private spending improved the program would shrink significantly.

It would also eliminate the unemployment benefit and several billion currently being spent on managing the unemployed (Job Services Australia!).

This is only the first step and, not, by any stretch of the imagination the only initiative that I advocate to restore full employment. As you will see I propose major spending initiatives, which would prioritise the creation of skilled jobs throughout the public sector with major spill-overs to the private sector.

For those who think that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is a one-trick pony – the JG – then I advise you to read all our work and understand where the JG fits into the overall policy schema.

Note in Table 1 that I suggest a deficit of $A70 billion in the coming financial year. That is a fiscal shift of around $A45-50 billion depending on what this year’s deficit comes in at. The JG will cost only $A22 billion. That leaves a lot of other spending opportunities.

Further you will note below that I propose billions of cuts in areas which we might describe as corporate and high-income welfare. Again the fiscal room that these measures would create are substantial.

There are other glaring spending shortfalls that I would remedy over the next several budgets.

Some spending initiatives

Among other things that need attention, I would fund:

More public hospital beds

Noting below that I propose to end all subsidies to private health insurance and payments to private hospitals

Large increases in the public education budgets

I consider Gonski’s $A9 billion recommendations to be the minimum that is required in the coming year. The government thinks it can spread these out over 5-6 years. There has been a massive degradation of our public schools, which still educate around 70 per cent of our children.

At present the Federal government spends more than $A8.5 billion on non-government schools. In 2011-12, it is estimated that the Federal payment per student is $A6202.9 for non-government school students and $A1,963.16 for students in government schools. It is true that the State government provides more support for state schools.

But since when has it been the Federal government’s responsibility to even up the funding to ensure the children from the highest income families get a massive public handout?

Improved urban public transport

Our cities are becoming unworkable because of years of neglect of public transport systems combined with a fetish for the motor car.

Governments, obsessed with surpluses, have under-invested in public transport. They build a freeway to alleviate traffic congestion and this just attracts more cars onto the road. We need major investments in mass-transit and we should stop thinking about these systems in terms of whether they can be commercial propositions.

I would make these systems free, ensure there is high-speed free wi-fi available and sit back and watch the cars disappear off the roads.

Cure the massive shortage in public housing

National Shelter’s – Housing Australia factsheet – tells us that:

- In 2009-10, 60% of lower-income rental households in Australia were in rental stress.

- In 2010-11, only 5.2% of homes sold or built nationally were affordable for low-income households.

- In 2009-10, there was a shortage of 539,000 private rental dwellings that were both affordable and available for renters with gross incomes in the bottom 40% of income distribution.

- here were 224,876 applicants waiting for social housing in 2012.

- There were estimated to be 105,237 homeless people on census night in 2011 – a 17.3% increase from 2006

I would motivate a major shift in philosophy in public housing provision and expunge the neo-liberal bias that blames the victims for their circumstances.

The combination of deficient spending in our schooling system and persistently high unemployment has generated an under-class in Australia.

No nation that pretends to be advanced should tolerate this. Billions of dollars are need to redress this poverty of housing in the land of plenty.

Fast track the very fast train project

While this – Project – will take years to complete it should receive federal priority and funding fast-tracked.

Fund research and investment in renewable energy

Instead of pouring billions into the clean coal pit to buy-off the coal industry the federal government should prioritise the closure of carbon-based power generation and invest in renewables with the aim of becoming totally reliant on this form of energy by the end of the current decade.

Acknowledge our commitment to UN conventions with respect to ODA

In 1970, the 25th Session of the General Assembly of the United Nations passed a – Resolution on Financial resources for development – (Paragraph 43) that said:

In recognition of the special importance of the role that can be fulfilled only by official development assistance, a major part of financial resource transfers to the developing countries should be provided in the form of official development assistance. Each economically advanced country will progressively increase its official development assistance to the developing countries and will exert its best efforts to reach a minimum net amount of 0.7 percent of its gross national product at market prices by the middle of the decade.

The UN agreed that while “developing countries must, and do, bear the main responsibility for financing their development” it was still beholden on each “economically advanced country” to provide substantial resources by way of overseas development aid to assist nations that were less well-off.

Most recently, the – Report of the International Conference on Financing for Development – which emerged out of the Monterrey, Mexico meetings of the United Nations (March 18-22, 2002) said that (Paragraph 42) in the context that “a substantial increase in ODA and other resources will be required if developing countries are to achieve the internationally agreed development goals and objective” and:

In that context, we urge developed countries that have not done so to make concrete efforts towards the target of 0.7 per cent of gross national product (GNP) as ODA to developing countries …

The meeting also noted “that ODA will still fall far short of both the estimates of the flows required to ensure that the millennium development goals are met and the target of 0.7 per cent of gross national product”.

Australia is at 0.35 per cent – half the agreed target.

In 2007, in recognition that Australia had dramatically failed to meet is international obligations in meeting the agreed 0.7 per cent target, the Federal Government embarked on a strategy to steadily increase our ODA/GNI ratio to 0.5 per cent by 2016-17 (ever the nasty and mean little nation!). This was a doubling of the existing ratio.

At present the ratio is at 0.35 after a few years of increase after the 2007 commitment. The improvement in the ratio has now stalled.

In the subsequent May 2012 Federal Budget the Government announced it would cut $A3 billion from the ODA budget over the next four years. The Budget allocations are summarised in this – Document.

There you see that the Government allowed for spending to increase from $A4.8 billion to $A5.1 billion (an estimated 4 per cent real increase) but the ODA/GNI ratio would remain static at 0.35 per cent.

So while the aid budget still increased in nominal terms the actual increases necessary to bring the ODA/GNI ratio up to even 0.5 per cent would be twice the amounts actually budgets for over the relevant time horizon.

In that context, and reduce our national shame for being so mean and tricky I would allocate $A12.5 billion (or thereabouts) in the 2013-14 Budget to ODA, which would finally see us honouring the commitment we made in 1970 but have avoided ever since.

Some spending cuts/tax changes

There is also massive waste and inequity in the current fiscal policy mix.

Many of these targets fit into what I call the blurring of the public-private boundaries under neo-liberalism, where profits are pocketed privately but losses are socialised as handouts. This system is deeply ingrained in Australia and should be remedied.

Capitalists talk about their entrepreneurial talents. Well, risk and return go together. Let them take the risks and pocket the returns subject to normal taxation. But the risk shouldn’t be subsidised at all by the public purse.

Over the next few budgets I would abolish some of the following anomalies:

- All federal funding to non-government schools ($8.3b)

- The tax concessions relating to negative gearing ($5.2b)

- The private health insurance rebate ($4.5b)

- All handouts to the mining sector ($2b)

- All private hospital funding ($5b)

- All general corporate welfare handouts ($9.8b)

- Eliminate the tax concessions for superannuants over 60, family trusts and the like.

- The Mining tax should be redesigned to reflect the economic motivation as a resource rent tax with zero concessions and zero handouts to offset the impact.

The list is indicative. There are many more public spending holes that channel funds to high-income earners or corporations (which end up as incomes for high income earners anyway).

I would set up a Committee to determine all forms of corporate and high-income welfare and in the 2014-15 Budget any remaining examples that I didn’t phase out in the coming year would be terminated.

Conclusion

I appreciate that the argument here runs counter to the mainstream. In that vein, I have prepared a number of background briefing documents to help you understand the reasoning behind this short Fantasy Budget contribution. Please go to – Fantasy Budget – for more information.

This ends my little mini-series on the Fantasy Budget for 2013-14. Regular blog analysis will resume tomorrow.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Great post Professor,

Although I agree with the anomalies you would abolish, I am sceptical that the abolition of federal funding to private schools is a political achievable reform. The strength of the Australia fetish with this item rivals its obsession with the motor car.

On a different topic, has any consideration been given to the provision of an online course (fee paying of course) to accompany the new textbook?

Bob

I may have more to say later, I have considered the abolition of funding to non-government schools in the past and I determined the abolition of funding beyond anything that is not part of the essential [national] curriculum. Education is a public good but if you want to run it privately, it should be subject to private enterprise and not be reliant on the public teat.

A profoundly great budget proposal Professor.

It will be very interesting to see how it is received.

Bill –

That doesn’t tell you much about the budget deficit.

Currently the RBA regard any sign of economic success as an unacceptable inflation risk, and move to stamp it out with higher interest rates. We could do everything you suggest and the RBA could still ensure that there’s an output shortfall and idle labour resources. Conversely if the RBA halved interest rates, the private sector would not be so keen to net save, foreign banks wouldn’t be so keen to park their money in Australia, and our dollar would fall, improving our trade balance. Labour resurces would be much better utilized, yet there would be a smaller deficit or possibly even a surplus.

This doesn’t mean your spending suggestions aren’t worthwhile, but they should be considered on a case by case basis. I’ve yet to see any detailed comparisons of the effects of government spending increases and interest rate cuts. Do you know of any?

Bill –

I suggest you rephrase that, as at the moment you’re making it sound as if you’re trying to bust the myth that inflation is the risk of insolvency!

As for your plan to stop subsidizing private schools and hospitals, why should the Federal government care whether or not the school is owned by a state government? Surely it’s the work they do that’s important, not who owns them?

“Conversely if the RBA halved interest rates, the private sector would not be so keen to net save,”

Not sure you can imply that. Across the globe interest rates have been cut and the result is more saving, exchange rates have fallen and there has been no more trade.

It’s not that simple – because indirect measures have indeterminate distribution characteristics. That’s the problem with playing the interest rate game.

Yes the RBA should do what the government tells it to do, the pretence of ‘independence’ should be given up and monetary policy fighting fiscal policy should never happen. Rates should be lower and banks more constrained.

But the classical behavioural ideas of what monetary policy does cannot be relied upon. Almost all of them have an underlying assumption that you can steal an amount of momentum from elsewhere on the globe.

Re the effect of interest rate changes on investment, here is one study says there is no effect. Another says there is an effect on property investment when property prices are high, but not when they are low, plus there is no effect on industrial property investment. See respectively:

http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/1814283?uid=3738032&uid=2129&uid=2&uid=70&uid=4&sid=21102247716357

http://realestate.colorado.edu/storage/publications/thibodeaupeng_interestrate.pdf

But the real flaw in interest rate adjustments is this: if stimulus is needed, why stimulate just one part of the economy, i.e. borrowing and investment? You might as well stimulate just car manufacture, restaurants and massage parlous and hope for a trickle down effect that benefits the rest of the economy.

Neil Wilson, it is that simple and it’s nothing to do with stealing momentum. Do you really not understand? Most countries have hsd more net saving despite lower interest rates, because they’re in a situation where cuts in interest rates are insufficient to get the economy back to capacity (pushing on a string is the metaphor most commonly used). Australia is not in that situation.

The problem isn’t the RBA’s independence, it’s the government failing to tell it to change policy.

Aidan,

When the money supply is endogenously determined fiscal policy makes a lot more sense than monetary policy does if you are attempting to stimulate the economy.

To argue that monetary policy is the better tool would be to assume that the money supply was exogenously determined.

In IS-LM terms the case of a vertical LM curve with a downward sloping IS curve is what you seem to be imagining.

Alternatively, an upward sloping LM curve and a horizontal IS curve will also render fiscal policy useless as it will completely crowd out private investment

The good news though is that neither of these cases apply to the modern money economy we live in.

For the record. I’m not a fan of IS-LM.

“Do you really not understand?”

I understand you have a near religious belief in the power of interest rate cuts to make things magically better. I’m not convinced at all that the distribution of that policy on its own is helpful – particularly not when you have a government obsessed with surpluses.

Alan Dunn, I’m not claiming that monetary policy is an intrinsically better tool, I’m saying that a change in monetary policy is what the Australian economy needs most right now. It has little if anything to do with assumptions of how money supply is determined; rather there are big problems in the Australian economy that are caused by monetary policy, and changing monetary policy is the best and most efficient way to solve the problem.

Aidan,

You might like to read the Reserve Bank Act 1959.

In particular have a look at section 10

Section 10 – Functions of Reserve Bank Board

(1) Subject to this Part, the Reserve Bank Board has power to

determine the policy of the Bank in relation to any matter, other

than its payments system policy, and to take such action as is

necessary to ensure that effect is given by the Bank to the policy so

determined.

(2) It is the duty of the Reserve Bank Board, within the limits of its

powers, to ensure that the monetary and banking policy of the

Bank is directed to the greatest advantage of the people of

Australia and that the powers of the Bank under this Act and any

other Act, other than the Payment Systems (Regulation) Act 1998,

the Payment Systems and Netting Act 1998 and Part 7.3 of the Corporations Act 2001, are exercised in such a manner as, in the

opinion of the Reserve Bank Board, will best contribute to:

(a) the stability of the currency of Australia;

(b) the maintenance of full employment in Australia; and

(c) the economic prosperity and welfare of the people of

Australia.

To see what actions the government can take to bring the RBA back into line (assuming they want to see section 11 of the Act.

http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/download.cgi/cgi-bin/download.cgi/download/au/legis/cth/consol_act/rba1959130.rtf

When you look at the composition of the RBA board it’s not difficult to see why the RBA does all it can for the richest one percent and lays the boot into the working and middle classes.

Chairman: Glenn Stevens

Governor since 18 September 2006

Present term ends 17 September 2013

Reappointed from 18 September 2013 until 17 September 2016

Chairman – Payments System Board

Chairman – Council of Financial Regulators

Member – Financial Stability Board

Deputy Chairman: Philip Lowe

Deputy Governor since 14 February 2012

Present term ends 13 February 2019

Martin Parkinson PSM

Secretary to the Treasury

Member since 27 April 2011

Member – Council of Financial Regulators

John Akehurst

Member since 31 August 2007

Present term ends 30 August 2017

Chairman – Reserve Bank Board Audit Committee

Director – CSL Limited

Director – Origin Energy Limited

Director – Securency International Pty Ltd

Director – University of Western Australia Business School

Roger Corbett AO

Member since 2 December 2005

Present term ends 1 December 2015

Chairman – Reserve Bank Board Remuneration Committee

Member – Reserve Bank Board Audit Committee

Chairman – Fairfax Media Limited

Chairman – Mayne Pharma Group Limited

Chairman – PrimeAg Australia Limited

Director – Wal-Mart Stores Inc

John Edwards

Member since 31 July 2011

Present term ends 30 July 2016

Member – Reserve Bank Board Remuneration Committee

Adjunct Professor – John Curtin Institute of Public Policy, Curtin Business School, Curtin University

Adjunct Professor – University of Sydney School of Business

Visiting Fellow – Lowy Institute for International Policy

Member – Australian Workforce and Productivity Agency

Kathryn Fagg

Member since 7 May 2013

Present term ends 6 May 2018

Heather Ridout

Member since 14 February 2012

Present term ends 13 February 2017

Chair – AustralianSuper Trustee Board

Director – Australian Securities Exchange Limited

Director – Note Printing Australia Limited

Director – Sims Metal Management Limited

Catherine Tanna

Member since 30 March 2011

Present term ends 29 March 2016

Member – Reserve Bank Board Remuneration Committee

Chairman – BG Australia

Chair – Queensland 20 (Q20)

Member – Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games Corporation Board

I would also increase funding by Fed Govt in medical research with all resulting patents etc being owned by the Govt. Successful researchers would be rewarded with a bounty. The govt would then licence generic drug companies to produce and sell the drugs on either a cost plus basis (i.e. govt sets the profit margin), or alternatively on a price minus basis (i.e. the drug company must sell for no more than a certain price). Alternatively, it could be put into the public domain free of cost (or maybe say after 5 or 10 years). This would reduce the funding required under the PBS, improve the welfare of society, and generate efficiencies (less time spent by researchers applying for funding). It could also become part of our overseas aid budget (either provide manufactured drugs or the patents for local cheap manufacturer).

As part of the package I would repeal the R&D tax incentives because that R&D probably will be undertaken anyway, and is using public funds to create private monopolies.

I would take this approach for all research – direct public funding with the results publicly owned and used for public benefit.

Critics will say that non-private ownership of research results will reduce/eliminate any incentive for research to be undertaken. To which I say bull. Dr Ian Fraser did not set out to find HPV vaccine to make money by exploiting his patent (or actually part of the patent – the rest is owned by the medical companies that financed his research). He did the research to solve a problem.

Neil Wilson –

Then you misunderstand. It is no more magical than the power of government deficits to make things better. The reason I may seem to be obsessed with interest rate cuts is because Bill’s been neglecting to mention them. He’s clearly shown that it’s the combination of interest rates and the size of the deficit/surplus (and the external balance) that drives the outcome, yet most of what he writes ignores the contribution of interest rates.

Nearly everyone knows high interest rates can cause a lot of harm. Most Australians remember the Keating recession, which was the direct result of high interest rates in the late 1980s. What fewer people are aware of is Australia’s current problem: because interest rates here are higher than the rest of the world, it’s artificially raising the short term value of the Australian dollar, making it extremely difficult for Australian manufacturers to compete with their overseas counterparts. Increased government spending can compensate for diminished economic activity, but risking so many manufacturers going bust because of short term problems that occur too suddenly to adapt to isn’t a problem that increased government spending can easily solve. And denying those same manufacturers the benefit of low interest rates to fund the upgrading of their equipment is a recipe for disaster.

The theoretical benefits of low interest rates are huge. For instance the high fixed cost of solar power would cease to make it less economically viable than fossil fuels. So I’d rather not see the interest rate climb when the economy takes off. I’d rather have interest rates constantly low (with a broad based land value tax preventing them from causing a land price bubble) and a government policy of using surpluses the way they currently use interest rate rises (to control inflation in the boom phase). I actually got that idea from Bill, who subsequently seems to have disowned it!

Bill has also made the valid point that a lot of the Costello surplus was the result of underinvestment in infrastructure. That’s something that shoudn’t be replicated, so I’d like to see an alternative framework for cost benefit analyses using the the true economic effects instead of the financial basis that’s normally used at present. Unfortunately Bill’s shown no interest in developing one – so if you find anyone who is, please let me know!

Bill,

you’ve got a rational behind the size of the deficit, but I didn’t notice anything about how it should be financed. Is the idea to finance the deficit by selling bonds to the private sector, or borrow it from the reserve bank (i.e. keystroke generation of currency)? If a mixture of these two is to be used, then how do you go about deciding what the mixture should be?

I suppose any use of the keystroke method amounts to some degree of QE, although not initiated by the reserve. The reserve might “steralise” this expenditure by selling government bonds, although I note that the RBA has more bank bonds these days rather than government bonds, so they might not be able to steralise as exactly as most central banks could. But anyway, you might take this as a question about QE as much as anything.

An excellent budget. Australia would become an exciting and dynamic place if these MMT policies were implmented. Bill was limited for space. He mentioned wifi but he did not mention Broadband or maybe I missed it by reading a little too fast. Australia has slipped to 46th on the world broadband ranking. That is a disgrace and indicative of the damage to infrastructure building and employment prospects that is done by throttling the economy with the budget surplus fetish.

I know Bill is very busy but I would like to see him interact and reply more to posts. Perhaps he could assign a trusted student or research assistant to some of this work if he is fortunate enough to have such a person paid for in his institutional budget. People post with questions, quibbles, disagreements, misunderstandings, requests for enlightenment and so on. It would be good to see more elaboration and debate on these issues.