I am in the final stages of moving office and it has been a time…

RBA decisions bring out the economic bogans

The Reserve Bank of Australia cut interest rates yesterday – to the lowest level since the 1950s – as an emergency measure to combat a failing economy, which is being pushed over the cliff by the excessively tight fiscal policy. This is only the second time that the RBA has altered interest rates during an official election campaign. Last time, they hiked them to the disadvantage of the then conservative government who had claimed interest rates would always be lower under them than under the Labor government. This time they cut them to the advantage of the Labor government (which is also pretty conservative). It gave the news outlets and current affairs programs something to do lat night. The problem is that what they did with the stories illustrated how poor the state of economic debate is in this country. It is always an unfortunate side effect of the RBA decisions that they bring out the economic bogans, even if they dress up a bit to disguise their anti-intellectuality.

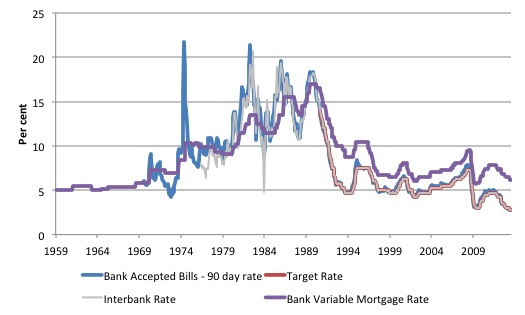

The following graph shows various interest rates since January 1959. The Cash or Target Rate (which was first published in August 1990 is virtually identical to the Interbank Rate (the rate that banks lend reserves to each other), given that the RBA manages the reserves to ensure it hits its target each day.

There are only rare occasions when the Interbank Rate varies from the Cash Rate and then the differences are small. Note that the variable mortgage rate was highly regulated before the 1980s

It is obvious that the current target rate is at historically low levels, which is good news for borrowers but bad news for those who rely on fixed incomes. The net effect on demand is unclear given these distributional conflicts although the RBA clearly thinks it is running a stimulatory monetary policy. I doubt the extent of that stimulation.

It is also worth nothing that the RBA prematurely tightened rates in 2009 on the back of its ridiculously optimistic growth forecasts. They were as caught up in the Government’s nonsensical surplus rhetoric as the Treasury was. Both were pumping out growth forecasts that were never going to be realised given the contractionary policy regime that was being imposed. Neither policy agency seemed to understand that households and firms are not going to return to the credit binging days that preceded the crisis.

The – Statement by Glenn Stevens, Governor: Monetary Policy Decision – said:

In Australia, the economy has been growing a bit below trend over the past year. This is expected to continue in the near term as the economy adjusts to lower levels of mining investment. The unemployment rate has edged higher. Recent data confirm that inflation has been consistent with the medium-term target. With growth in labour costs moderating, this is expected to remain the case over the next one to two years, even with the effects of the recent depreciation of the exchange rate … The Board has previously noted that the inflation outlook could provide some scope to ease policy further, should that be required to support demand. At today’s meeting, and taking account of recent information on prices and activity, the Board judged that a further decline in the cash rate was appropriate.

So while the RBA is formally pursuing an inflation target, it is also now seeing its role to support aggregate demand – that is, a traditional counter-stabilisation function.

The issue then becomes – is monetary policy the best means of supporting demand? The answer, which I have given (and explained) many times, is no!

The Government has continually claimed that by running a tight fiscal policy they have set up the conditions for record low interest rates. The previous Treasurer used to say that the fiscal austerity has allowed the RBA to cut rates. That argument is disingenuous in the extreme.

The Government’s strategy has been to deliberately create unemployment in the non-mining regions so that the idle resources could then service the mining boom. Yet, the mining boom is over (at least the construction phase) and non-government spending is not strong enough to support trend growth.

So what has been happening is that the Government has been driving the economy into the ground leaving the RBA to backfill the damage with an arguably inferior policy tool (cutting interest rates). That is a far cry from the way the Treasurer constructs the events. Fiscal policy should not be used to deliberately create unemployment when the economy is well below full capacity.

Pro-cyclical fiscal policy changes are the anathema of responsible fiscal management. Discretionary changes in fiscal policy should typically be counter-cyclical – to manage output gaps. The only time an expansionary discretionary fiscal change should be pro-cyclical is when growth is positive but not strong enough to achieve full employment. Once capacity is reached, fiscal policy should counteract non-government spending changes.

With the federal election looming, the ABC’s flagship evening current affairs program, 7.30 is featuring economic matters each night. But, as I have noted in the past, the presenter, Leigh Sales, knows very little about macroeconomics and her questioning (or lack of relevant questioning) means that myths are perpetuated and the viewers are misled as a consequence.

The same goes for her Canberra off-sider, Chris Uhlmann. Both seem to give privileged access to the Director of Access Economics, a Canberra-based consulting company, which sings from the neo-liberal hymn sheet. The company is continually telling us about how bad deficits are, that the government is broke, that the deficit is broke and all the rest of it.

Access Economics was one of the private groups that had forecast that a budget surplus would materialise last financial year. I considered their forecasting prowess (or almost total lack of it) in this blog – A Budget that reduces growth and increases joblessness – for no sound reason

On September 28, 2011, News Limited carried the story- Access Economics’ Budget forecast is pessimistic, says Wayne Swan which said:

Access expects a surplus of $3.8 billion in 2012/13 compared with Treasury’s forecast of $3.5 billion, but a $1.8 billion deficit in 2013/14 against an official prediction for a $4.5 billion surplus.

They were significantly wrong for both years.

By late 2011 (November) as the data was showing their predictions were unsustainable, Access revised their estimates to a small deficit for 2012-13 (Source) and progressively altered their forecasts as each previous forecast looked to be an deeply flawed assessment.

Late last year (November 2012), the ABC news sprayed the following headline across the daily news – Access Economics forecasts budget deficit.

The only news at that time was that Access had changed their minds when it was obvious they had completely missed what was happening in the economy (and why), which of-course the ABC didn’t choose to report.

Anyway, the first segment on 730 last night – Interest rates fall as electioneering picks up – once again featured the Director of Access Economics and it is clear humility is not his thing.

The segment was reported by Chris Uhlmann and after some introductory banter about what the political leaders were doing on the campaign trail, he began an interview with the Access director (Chris Richardson).

The Access Director was asked what the low interest rates said about the economy and replied:

They’re headed down because the economy is soft. And it’s been soft for a while because of a strong Australian dollar, it’ll stay soft because the big mega mining projects are now winding down, but neither of those things you know, earlier strength of the dollar, the next phase, the wind down of the mining boom construction, neither of that is due to Canberra. All of it is due to China.

The Government’s own – Economic Statement – (released August 2013) – showed that public final demand contracted by about 1.5 per cent in 2012-13 at a time private sector final demand was also not as strong as previously forecast.

That has everything to do with Canberra (and the state/territory governments).

Further, the factors identified have been obvious for the last few years and the correct policy response would have been to abandon any plans to achieve a budget surplus and instead expand the deficit in a discretionary fashion. The deficit has risen but largely due to the automatic stabilisers (massive loss of tax revenue as the economy slows).

After some further questions to politicians about the credibility of deficit forecasts and other meaningless issues like that, the reporter turned back to his “economics expert”, the Access Economics Director.

The transcript went like this:

CHRIS UHLMANN: No matter who wins the election, the task of making the books balance will be difficult for any future government.

CHRIS RICHARDSON: Whoever wins has to repair the Budget. The official forecasts are for a small surplus. But they’re very dependent on two things. Number one, if China slows further that surplus disappears very fast. Number two, those official forecasts stop just four years from now, and it’s beyond that that things like these new policies, DisabilityCare, schools, the rest of it, get really expensive. We run the risk that even if we do manage to make it to surplus it’s five minutes of surplus sunshine. Whoever wins faces a big expensive Budget repair task.

The terminology tells you all. “Repair”, “Surplus Sunshine”, “Expensive repair task”, etc

The budget is not a limb that can be broken. It is not a machine that wears out. A deficit equivalent to 2 per cent of GDP might be a very irresponsible outcome or the perfect public sector contribution to final demand. It all depends.

A surplus of 5 per cent of GDP might be required for sound fiscal management but it also could be the sign of a very destructive policy position. It all depends.

What sense does the meaning of the work “repair” have in this regard? None at all. What sense does the expression “Sunshine”, which we usually take to mean as indicating warmth, have in relation to a surplus? None at all. A surplus could be a reasonable position or a totally inappropriate position for the government to be in.

Would a surplus be good, in the context of an external deficit (which Australia will run at around 3-4 per cent for the indefinite future) and a private sector balance (given the rise in household saving to 10 per cent of disposable income and the decline in investment growth)?

The answer is that such a position would be unsustainable and the economy would soon see recession and high unemployment and …. a budget deficit brought about by the negative income shifts. There would be no sunshine in that outcome.

The point is that these loaded terms have no meaning when we talk about budget positions and outcomes.

There is no “big expensive Budget repair task” looming for any future government. What is looming is an ageing population – which presents a productivity challenge. To maintain real standards of living we are going to have get more out of less and creating stagnant growth and rising unemployment by cutting discretionary net public spending now is the least obvious way of achieving that.

We need massive public investments in education, public infrastructure (such as the National Broadband Network) and the like to sustain higher productivity growth rates in the future. That means we need larger deficits now and into the future. The massive amount of excess productive capacity at present means we can easily “afford” to run larger deficits.

Afford here means that we have idle real resources that can be brought back into productive use by appropriately targetted government spending.

The idiocy in the interview continued:

CHRIS UHLMANN: So whoever’s in government after September seven, what are the kinds of decisions that they will have to make?

CHRIS RICHARDSON: You’ve got to cut spending and raise taxes. Both are unpopular. Already we are in a phase where the promises that have been made by past governments, the current one, previous one, are costing more than the Budget will support so it’s showing up as a deficit. This is a campaign where I want to see as few promises as possible because we already can’t pay for the promises that both sides

What Richardson should have said is this – “You’ve got to cut spending and raise taxes” if you want to engineer a massive recession and push unemployment up towards 8-10 per cent and lock out the teenagers from the labour market indefinitely.

Further, there is no economic meaning to the statement “costing more than the Budget will support”. Perhaps that is a political statement, in which case what qualifications does Richardson have as a political scientist? The answer to that question is clear.

It certainly has no economic sense. The Budget can be whatever it is. The government can buy whatever is for sale in Australian dollars. It can run very small or very large deficits in absolute terms or relative terms without blinking. The only sensible relationship that we might consider in terms of the budget is whether it is calibrated to the real resources that the non-government sector is not using.

If there are real resources idle then the budget deficit can always increase – and should.

The second segment on the 730 Program – Joe Hockey says rates cut reveals struggling economy – featured the Opposition (conservative) Shadow Treasurer.

Hockey’s assessment of the direction of monetary policy was correct but given the economic reasoning that followed, that correct conclusion was clearly accidental. It is amazing that the political process could produce someone who aspires to leadership in the area of macroeconomic policy leadership who is as incompetent as Joe Hockey.

This is the correct statement (which is a collection of a number of responses he made early in the interview):

… they’re not cutting interest rates because the economy is doing well. Interest rates are being cut to 50 year lows because the economy is struggling … if anyone thinks that the Reserve Bank acted today because the economy is doing really well, and Labor’s doing a terrific job running the economy, they’d be deluding themselves.

There is no other way of interpreting the 12 cuts in the Cash Rate since October 2011, when it became clear that inflation was falling and employment growth was virtually zero. Since that time real GDP growth has fallen well below trend – not a “bit” below as the RBA Statement notes.

The RBA has repeatedly stated that it is worried about the decline in aggregate demand as fiscal policy contracts and the investment boom associated with the mining sector fades.

The ABC Interviewer (Leigh Sales) then asked the Shadow Treasurer:

LEIGH SALES: Let me just ask you a broad economic question. At what point is in the electoral – sorry, at what point in the economic cycle is running a deficit sound economic policy?

JOE HOCKEY: Well, it’s obviously sound if you have a dramatic drop in growth and you need to stimulate the economy with fiscal stimulus. Now whether that is appropriate or not depends on a whole range of factors. Firstly, one of the factors you’ve got to have is you’ve got to have the capacity to stimulate. And one of the reasons I’m most concerned about debt and deficit and Kevin Rudd has no regard for it is because there is little capacity now for fiscal stimulus because the Government has borrowed now up to $400 billion and it’s leaving us with ever going deficits.

At this point, the Shadow Treasurer loses contact with macroeconomic reality.

Yes, the government should stimulate the economy when there is a dramatic drop in growth. Correct. But by that very logic it makes no sense in the context of a currency-issuing government such as Australia to then say that the “capacity” to stimulate is questionable.

The capacity to stimulate is defined by the real output gap – by the amount of productive capacity that is currently un(der) utilised because aggregate demand is deficient.

So when there is a “dramatic drop in growth” there is always spare or idle productive capacity. The stimulus should be calibrated to reflect that idle capacity given estimates of the likely response by the private sector to the stimulus.

Any reference to the current budget balance (deficit or surplus) or the current level of outstanding debt (whether in absolute terms or relative to GDP) in assessing the capacity to stimulate is erroneous and discloses an ignorance that should disqualify the person from holding the high office of treasurer.

While the outstanding debt liabilities of the federal government are relatively small in historical terms they are irrelevant to assessing whether the Federal government has the capacity to increase net spending. It issues the currency – so it can always buy whatever is for sale in the currency it issues, including all the labour resources that are being wasted by the Australian economy at present (at least 13 per cent of the known labour force and then some – given that the hidden unemployed are not included in the labour force measure).

Further, whether there are continuous deficits implied into the future (these “ever going deficits”) is also irrelevant. Running surpluses provides the government with no extra funds to net spend in the future.

The Shadow Treasurer was then asked why the Opposition had “demonised” the use of deficits in the period after the crisis. Readers may recall that the Opposition actually claimed it would not have moved from surplus to deficit in 2008 as the crisis was emerging.

The response was that the Government “wasted people’s money”:

… Labor predicted and forecast they would be in surplus now and they did it on hundreds of occasions Leigh, and the reason why they’re not in surplus, when you actually look at the details of the figures, is they don’t know how to reduce their spending. And if you don’t reduce your spending when you’ve got record terms of trade, when you’ve still got five per cent unemployment or 5.5 per cent unemployment as the case has been, if you don’t run surpluses in those sorts of environments, when are you going to run a surplus and start to pay down $400 billion of debt?

Which is about as bad as it gets.

1. The Government could not deliver a surplus because the private domestic sector was intent on increasing its saving and the external sector was in deficit.

2. Had the government reduced their spending as much as the Opposition has been demanding the deficit would have expanded because the growth rate would have collapsed by more than it already has.

3. The reason the budget is still in deficit is because its revenue has collapsed due to the economy running well below trend real GDP growth. In part, that is because the Government pursued a surplus at a time that the other sectoral spending realities did not justify such a policy position.

The UK Guardian (Australian Edition) article yesterday (August 6, 2013) – The bottom line is, Joe Hockey can’t now admit to a deficit – provided the political insights to the lack of macroeconomic nous held by the Shadow Treasurer.

We read that the Opposition is avoiding committing to any particular budget balance aspirations (which is wise given the government doesn’t have control over what the budget outcome will be in any particular period).

But the Opposition’s position is not based on a sophisticated understanding of the impact of the cycle on the budget (via the so-called automatic stabilisers). Rather it is just afraid to say anything and instead is telling us that we can do the maths once it outlines its spending and revenue plans in the next few weeks leading up to the election.

The reality is clear. There will be Federal deficits for years to come and so both major political parties will have to do some spinning to overcome the impressions they have set that deficits will lead to a crisis of confidence.

Conclusion

We have another 5 or so weeks of this sort of nonsensical commentary.

It is going to be a long stretch!

730 Report Tonight

The 730 Report is running a segment tonight on unemployment and I did an interview for them yesterday. How much of that 20 minute interview survives is any one’s guess.

Tomorrow the July Labour Force data comes out and I will write about that.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“It is going to be a long stretch!”

Try not to destroy too many TVs with projectiles – no matter how high the temptation.

🙂

Bill, You ask “The issue then becomes – is monetary policy the best means of supporting demand? The answer, which I have given (and explained) many times, is no!”

Did those explanations include the point that the effect of interest rate adjustments and QE is distortionary, whereas fiscal adjustments needn’t be distortionary? Because I think the latter is a good point against monetary policy. E.g. interest rate cuts bring stimulus only via increased spending on investment goods. That’s a distortion that has to be unwound come the recovery.

The other reason the plonkers in power like monetary policy is that they suffer from deficit phobia, and monetary adjustments bring stimulus without increasing the deficit.

E.g. if government borrows and buys an office block that counts as deficit. In contrast, if the central bank prints money and buys the shares of the firm that owns the office blocks, that doesn’t count as deficit. (Cue, finance minister has an orgasm.)

This election is a choice between Homer Simpson and Montgomery Burns. Btw, it may help to elect homer if you could debunk the ludicrous crap regarding labor’s debt. If not, release the hounds may become official policy.

Can somebody explain the relationship between the bank 90 day rate and the official cash rate. I have noticed the close relationship before for the RBNZ,

http://www.rbnz.govt.nz/statistics/key_graphs/90-day_rate/

But to me it appears that the commercial bank 90 day rate leads the official cash rate. This also appears to happen in Australia.

I would have expected the central bank to be leading and for the 90 day rate to follow the OCR? If the central bank is following the 90 day rate, could the rates diverge sharply?

“The issue then becomes – is monetary policy the best means of supporting demand?”

It just depends how monetary policy is conducted? If the RBA is dependant on commercial bank lending to conduct MP into the system then maybe not. But that isnt the only way to conduct MP.

I heard Joe Hockey say “a rising tide lifts all boats” on the news last night. I had to turn the TV off and go practice my guitar after that 🙂

It has come to the point where I refuse to believe that even a man as dumb as Joe Hockey really believes the tripe he talks and is just hoping to use deficit hysteria to slash and burn the government’s already low social spending. I don’t think he even cares that this will cause bigger deficits. He’s got three years to get the job done, then Labor will be faced with three years of not being able to reinstate the programmes that have been cut because the “debt” will be that much higher.

Small technicality and I’m sure I am the exception to the rule

Through technicalities I’m a borrow on a fixed income and interest rate cuts are actually proving a boon for me.

Yes I’m sad about the lost interest income but I’m getting more money in my pocket which I desperately need this way.