Today (April 18, 2024), the Australian Bureau of Statistics released the latest - Labour Force,…

US labour market – bias towards toward job creation in below-average pay sectors

Last week’s (August 2, 2019) release by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) of their latest labour market data – Employment Situation Summary – July 2019 – reveals a steady labour market with month-to-month volatility. The US labour market is still adding jobs, albeit at a slower pace than last year. The unemployment rate remains low (at 3.71 per cent) and the participation rate has moved up a tick, which is a good sign. It is also clear that there is still a substantial jobs deficit remaining and considerable scope for increased participation. Significantly, the bias toward jobs in below-average pay sectors being produced in the recovery has intensified during 2019.

Overview for July 2019

- Payroll employment rose by 164,000.

- Total labour force survey employment rose by 283 thousand net (0.18 per cent).

- The seasonally adjusted labour force rose by 370 thousand (0.23 per cent).

- Official unemployment rose by 88 thousand to 6.063 million.

- The official unemployment rate was essentially unchanged at 3.71 per cent (+0.046 points).

- The participation rate rose by 0.1 points to 63 per cent but remains well below the peak in December 2006 (66.4 per cent). Adjusting for age effects, the rise in those who have given up looking for work for one reason or another since December 2006 is around 2,316 thousand workers. The corresponding unemployment rate would be 5.0 per cent, far higher than the current official rate.

- The broad labour underutilisation measure (U6) fell by 0.2 points to 7 per cent largely because of a substantial fall in the part-time for economic reasons cohort (the US indicator of underemployment).

Further, for those who are confused about the difference between the payroll (establishment) data and the household survey data you should read this blog – US labour market is in a deplorable state – where I explain the differences in detail.

Payroll employment trends

The BLS noted that:

Total nonfarm payroll employment increased by 164,000 in July, in line with average employment growth in the first 6 months of the year. In 2018, employment gains had averaged 223,000 per month. In July, notable job gains occurred in professional and technical services (+31,000), health care (+30,000), social assistance (+20,000), and financial activities (+18,000).

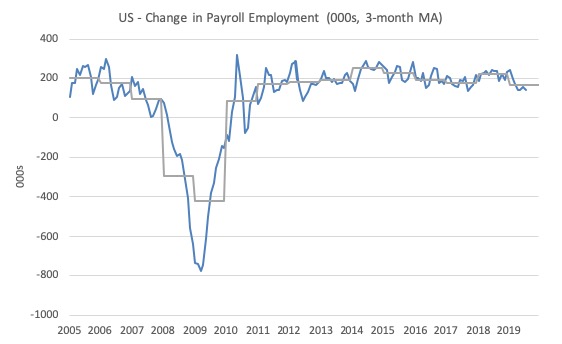

The first graph shows the monthly change in payroll employment (in thousands, expressed as a 3-month moving average to take out the monthly noise). The gray lines are the annual averages.

This month saw the change in payroll employment fall back to around the average monthly change for the year and well down on 2018 levels.

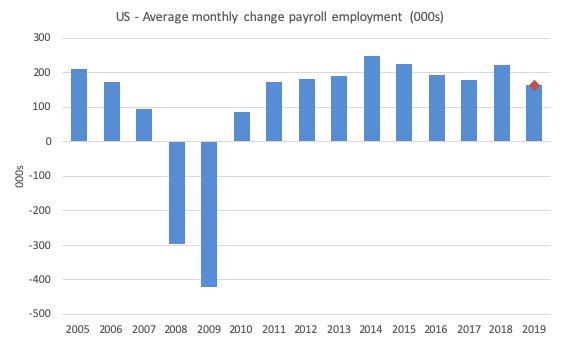

The next graph shows the same data in a different way – in this case the graph shows the average net monthly change in payroll employment (actual) for the calendar years from 2005 to 2019 (the 2019 average being for the first six months at this stage).

The red diamond is the current month’s increase.

The slowdown that began in 2015 continued through 2017 was reversed last year. The 2018 average was 223 thousand compared to 179 thousand in 2017.

So far the average for 2019 is 165 thousand. But within that lower first seven month average is considerable volatility on a month to month basis (in part due to statistical factors such as new bench-marking).

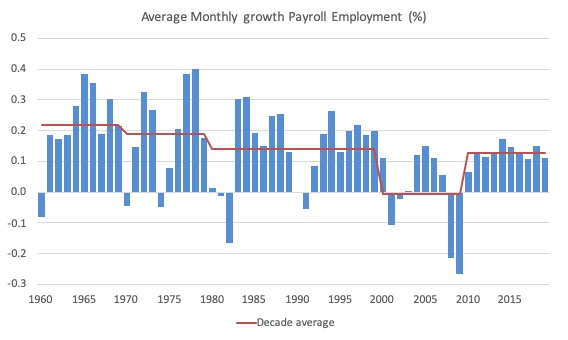

To put the current recovery into historical perspective the following graph shows the average annual growth in payroll employment since 1960 (blue columns) with the decade averages shown by the red line.

It reinforces the view that while payroll employment growth has been steady since the crisis ended, it is still well down on previous decades of growth.

Labour Force Survey – employment growth remains positive

Employment as measured by the household survey rose by 283 thousand net (0.18 per cent) while the labour force rose by 370 thousand (0.23 per cent).

As a result (in accounting terms), total unemployment rose by 88 thousand but the unemployment rate was largely unchanged at 3.71 per cent (+0.046 points).

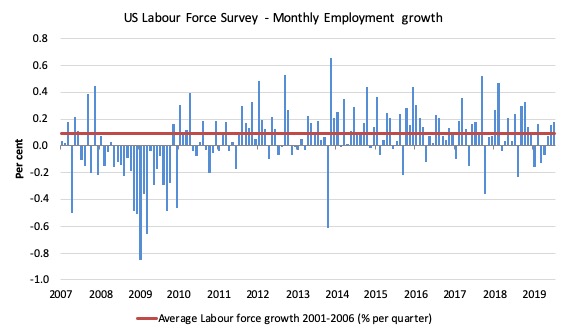

The next graph shows the monthly employment growth since January 2008. The red line is the average labour force growth over the period December 2001 to December 2006 (0.09 per cent per month).

Summary conclusion:

There is still no coherent positive and reinforcing trend in employment growth since the recovery began back in 2009. There are still many months where employment growth, while positive, remains relatively weak when compared to the average labour force growth prior to the crisis or is negative.

There are also months where employment growth is negative.

The last three months have seen increasing growth – which is a positive outlook

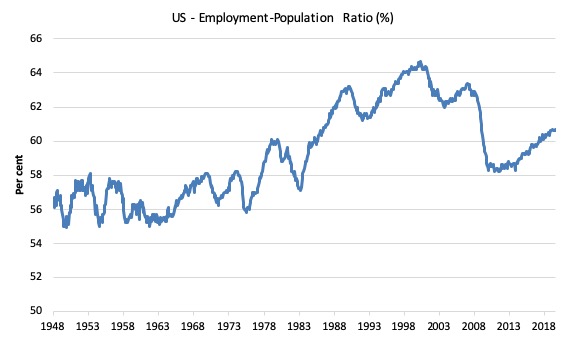

A good measure of the strength of the labour market is the Employment-Population ratio given that the movements are relatively unambiguous because the denominator population is not particularly sensitive to the cycle (unlike the labour force).

The following graph shows the US Employment-Population from January 1970 to July 2019. While the ratio fluctuates a little, the July 2019 ratio rose by 0.1 points to 60.7 per cent. This is a slight rise on the ratio that has held steady over the previous four months

This indicates a very steady situation – employment growing in proportion with the underlying population.

Over the longer period though, we see that the ratio remains well down on pre-GFC levels (peak 63.4 per cent in December 2006), which is a further indication of how weak the recovery has been so far and the distance that the US labour market is from being at full capacity (assuming that the December 2006 level was closer to that state).

Unemployment and underutilisation trends

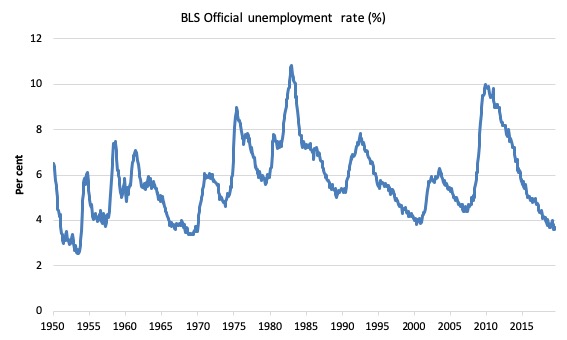

The first graph shows the official unemployment rate since January 1950 which is currently at 3.71 per cent.

It is clear that the US labour market is reaching unemployment rates not seen since the late 1960s (it is slightly lower than the most recent low-point in April 2000).

With inflation stable, the continued low unemployment rates make a mockery of official NAIRU estimates of full employment coinciding with an unemployment rate of 4.6 per cent.

The official unemployment rate is a narrow measure of labour wastage, which means that a strict comparison with the 1960s, for example, in terms of how tight the labour market, has to take into account broader measures of labour underutilisation.

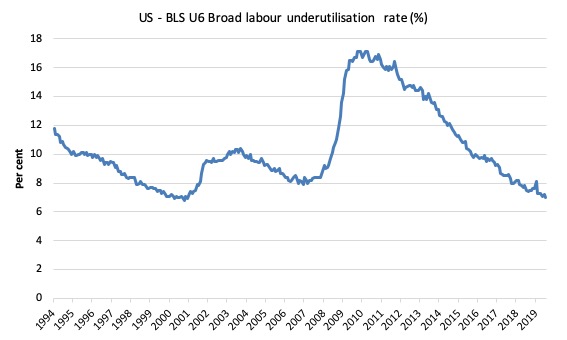

The next graph shows the BLS measure U6, which is defined as:

Total unemployed, plus all marginally attached workers plus total employed part time for economic reasons, as a percent of all civilian labor force plus all marginally attached workers.

It is thus the broadest measure of labour underutilisation that the BLS publish.

In December 2006, before the effects of the slowdown started to impact upon the labour market, the measure was estimated to be 7.9 per cent.

In July 2019 the U6 measure fell by 0.2 points to 7 per cent.

It was 8.1 per cent at the beginning of 2019.

The U-6 measure is marginally below the pre-GFC level but remains above the trough of the early 2000s when it was 6.8 per cent.

While it is signalling improvement, there is still some scope to go before full capacity is reached.

The low-wage bias continues

My feature on the US labour market this month focuses on tracking what I have called in previous blogs the low-wage employment bias in the US labour market.

To see the full methodology I employed in making these calculations please read the blogs – US jobs recovery biased towards low-pay jobs and Bias toward low-wage job creation in the US continues.

The question: Is there a bias towards low-pay jobs in the recovery in the US?

Answer: bias has eased but the proportion of below-average jobs has intensified over this year at the sectoral level.

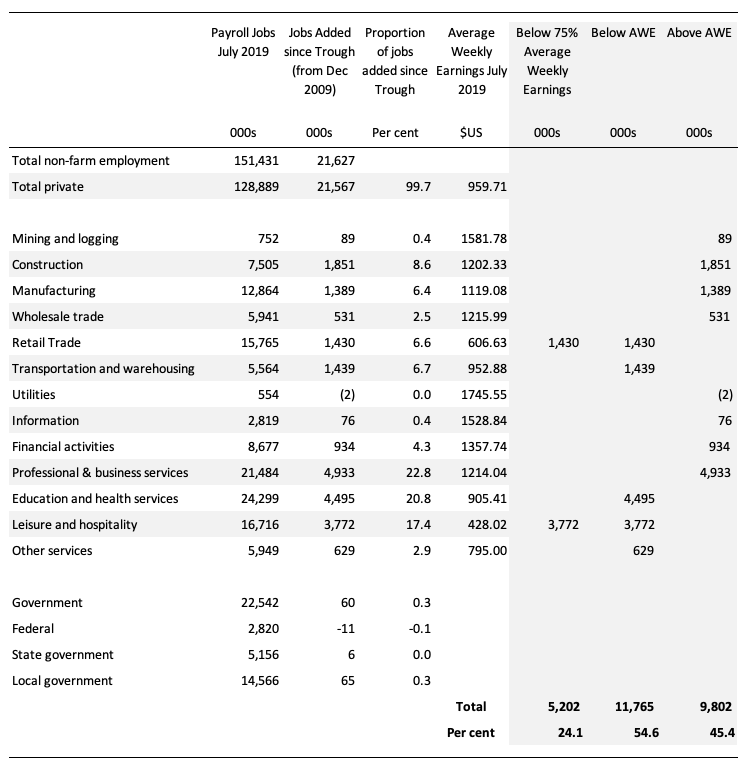

Effectively, since the recovery began in January 2010, there have been 21,567 thousand net jobs added to the US labour market (in the non-farm sector).

Of those net employment additions, 24.1 per cent have been what might be considered low-pay (defined as less than 75 per cent of average weekly earnings).

Previously, I have calculated what happened in the downturn with respect to the jobs lost in net terms and their pay characteristics (at a sectoral level).

Please read my blog – US labour market – improves in August but still no growth trend is apparent – for more discussion on this point.

The main conclusions were:

1. Peak US non-farm employment occurred in January 2008 (138,430 thousand) and the trough occurred in December 2009 (129,778 thousand).

2. The job losses for the top-level North American Industry Classification System (2012 NAICS) were calculated from peak (January 2008) to the trough (December 2009).

3. Overall 8.7 million jobs were lost – with 8.8 million lost in the private sector and they were only partially offset by the 94,000 net jobs added in the government sector.

4. In the downturn, 21.1 per cent of the jobs lost (net) were in sectors that paid on average below 75 per cent of the overall private sector average pay (that is, low-pay jobs).

5. 86.1 per cent of the total jobs lost in the downturn were in sectors paying above average pay.

The following table summarises what happened in the period from the trough to July 2019.

The second column shows the latest BLS payroll employment data as at July 2019. The next column shows the number of net jobs (in thousands) that have been added by each sector since the trough in December 2009.

The next column shows the percentage of those total jobs added by sector. You can see that the Private sector has added 99.7 per cent of the total net jobs added.

The fourth column shows the Average Weekly Earnings for each sector as at July 2019.

The final three columns split these job additions into their pay characteristics using the sectoral average weekly earnings and the same criteria as in the previous example.

The summary statistics for each ‘pay category’ (75% of Average Pay, Below Average Pay, Above Average Pay) are at the bottom of each column.

We find that:

1. Government employment has risen by 60 thousand (net) jobs with the federal government losing 11 thousand jobs.

2. 24.1 per cent of the total private jobs added could be considered low-pay. This proportion was 25.1 per cent in January 2008 and 25.4 per cent in December 2009.

3. However, the proportion of below-average jobs since January 2008 has increased – from 46.2 per cent of the total to 54.6 per cent in July 2019.

4. 54.6 per cent of the private jobs created (net) since the recovery began pay below average weekly earnings. That proportion was 47.9 per cent in October 2018.

5. The data shows that the low-paid private jobs that were lost in the downturn (1,843.8 thousand) have been more than added back (in net terms) in the upturn so far (5,202 thousand).

6. The above average pay private jobs that were lost in the downturn (7,528.8 thousand) have now been more than added back in net terms (9,802 thousand).

Clearly, this analysis is at the aggregated NAICS level and a richer story could be told if we used the two-digit and three-digit typed drill downs into the industry classification.

The US jobs deficit

The update to the participation shifts due to ageing also allows us to update our estimates of the US jobs deficit.

The current participation rate of 63 per cent is a long way below the most recent peak in December 2006 of 66.4 per cent.

Adjusting for the demographic effect would give an estimate of the participation rate in July 2019 of 65.3 per cent if there had been no cyclical effects.

This would give an adjusted unemployment rate of 5.1 per cent rather than 3.71 per cent, if all the new ‘hidden’ unemployed (since December 2006) were to be counted among the official unemployed.

To compute the job gaps, a ‘full employment’ benchmark of 3.7 per cent is used – which is the current rate.

I explain in this blog post – US labour market – strengthened in February but still not at full employment (April 13, 2018) – is the best case scenario given that I actually think the cyclical losses are much worse than I provide here.

Using the estimated potential labour force (controlling for declining participation), we can compute a ‘necessary’ employment series which is defined as the level of employment that would ensure on 3.7 per cent of the simulated labour force remained unemployed.

This time series tells us by how much employment has to grow each month (in thousands) to match the underlying growth in the working age population with participation rates constant at their January 2008 peak – that is, to maintain the 3.7 per cent unemployment rate benchmark.

In the blog post cited above (US labour market – strengthened in February but still not at full employment), I provide more information and analysis on the method.

There are two separate effects:

- The actual loss of jobs between the employment peak in November 2007 and the trough (January 2010) was 8,582 thousand jobs. However, total employment is now above the January 2008 peak by 10,693 thousand jobs.

- The shortfall of jobs (the overall jobs gap) is the actual employment relative to the jobs that would have been generated had the demand-side of the labour market kept pace with the underlying population growth – that is, with the participation rate at its January 2008 value and the unemployment rate was constant at 3.7 per cent. This shortfall loss amounts to 5,844 thousand jobs.

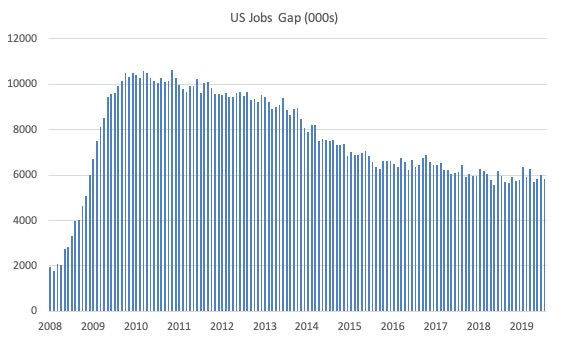

The following graph shows the US Jobs Gap, which depicts the gap between current employment and the level of employment that would have generated a 3.7 per cent unemployment rate, given current population trends.

The shortfall has been rising for the last three months.

This reinforces the conclusion we reached above that the US labour market, while now enjoying a low official unemployment rate has not fully recovered from the GFC.

Conclusion

The July 2019 BLS labour market data release for the US tells me that the US labour market has been relatively steady over the last few months despite some month-to-month volatility.

It is weaker than where it was at the end of 2018.

It is clear that there is still a substantial jobs deficit remaining and considerable scope for increased participation.

There is also a rising proportion of below-average wage jobs (at the sectoral level) being produced since this recovery began.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2019 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I wonder why nobody talks about regional differences. Just look at Alaska.

And EU, which is supposed to be 27 nation, half a billion people optimum currency area. Regional differences are huge!

MMT never talks about regional differences that are very real and you cannot expect Greeks to move to Norway and vice versa.

Dear John (at 2019/08/05 at 12:25 pm)

You assert:

Before you spread fictions, please do my readers the favour of reading the literature. I have specialised in regional impacts of macroeconomic policy decisions over the years and created a new geographic structure that has influenced the Australian statistician’s own geographic boundaries. There is a mountain of MMT work both in the academic and blog literature on regional issues.

best wishes

bill

Thanks Bill for continuing these series of windows on the US employment situation — the more often I see them, the better I come to understand how to interpret them.

Is there a way to measure “underemployment” (by which I mean the number of people employed part-time who would prefer full-time)? Is this already somewhere in your analysis and I have just not recognized it?

I ask because when I am struggling to convince my neoliberal friends of the pernicious effects of labor wastage, I like to use the term “un-and-underemployment” to emphasize that the problem goes well beyond official unemployment statistics.

Thanks again

John,

Re MMT and regional differences: one core goal of the MMT program is to avoid spending in ways that could result in unacceptable price inflation. Targeting economically depressed areas is a key element and is explicitly considered. An example is the Job Guarantee. It is a program available to all but is especially beneficial to people whose participation in the labour market is difficult and to regions that are depressed economically.

eg, I don’t if it’s the same in the US, but here in Australia, the Underutilisation rate = Unemployment + Underemployment. So for the US statistics, it’s the 7% underutilisation rate that you gives you the full picture.

If you want the Underemployment rate = Underutilisation – Unemployment. So with the US statistics, 7% underutilisation – 3.71% unemployment = 3.29% underemployment.

Thanks, Jan. But which measure is “underutilization”? I don’t think it’s the U6, because that’s total labor participation.

I will look at one in the series on Australian employment hereabouts and see if I can find the specific underutilization measure you are referring to.

Thanks again

eg, I think it is the U6 rate. It’s called the broad labour underutilisation measure, not total labour participation. Bill’s got that U6 = total unemployed, plus all marginally attached workers plus total employed part time for economic reasons, as a percent of all civilian labor force plus all marginally attached workers. Best of luck, anyway.